My career milestones

Student, Teacher Training College (Normal)

– Chapter 7

Student teacher Radin Mas School

– Chapter 7

Student, Raffles College

– Chapter 9

Teacher, Radin Mas School

– Chapter 10

Teacher, Raffles Institution

– Chapter 11

WORLD WAR II

– Chapter 13

Teacher, Raffles Institution

– Chapter 16 & 17

Grade 1 Specialist Teacher, English language, Raffles Institution

– Chapter 16 & 17

“Unofficial assistant” to Principal Raffles Institution

– Chapter 16 & 17

Acting Principal, Raffles Institution

– Chapter 16 & 17

Principal Beatty Secondary School

– Chapter 18

Acting Deputy Secretary B (Grade F) Ministry of Education

– Chapter 18

Principal Raffles Institution

– Chapter 18

Deputy Secretary/Deputy Director A (Grade E) Ministry of Education

– Chapter 18

Principal Beatty Secondary School: A rewarding experience (March – October 1955)

Soon after Young arrived in Raffles Institution to take over as Principal, the Ministry posted me as Principal, Beatty Secondary School. On 1 March 1955, I arrived early at the school, and was surprised to see pupils and staff lining the driveway, greeting me like guards of honour. It was heart-warming. For eight months, I enjoyed a delightful rapport with staff and pupils. Given a choice, I would have loved to remain there.

Before my arrival at Beatty there had been a student riot, causing damage to furniture. The security guard, who tried to keep out intruders on the field, had been beaten up. The pupils were disgruntled because in contrast to other schools, the previous Principal denied them use of the hall for badminton because he wanted to maintain the beautiful parquet floor. The staff resented the practice of shutting the school gate if they were late. I knew I had to win the hearts and minds of the pupils and staff.

I drew up a new set of reasonable guidelines for discipline. This included throwing open the hall for badminton, instructing the security guard to let outsiders play on the field on Sundays and public holidays and keeping them out when school was in session or when pupils were playing. I told him not to lock out teachers and pupils if they were late. Instead, they had to see me to give their explanations. Everyone was relieved and happy. There were very few latecomers and no intruders. To make up for the lack of a proper playing field I arranged with Victoria School for the use of their field for soccer, cricket and hockey matches. Pupils from other schools who had not been able to obtain admission to Pre University classes asked me to start a class for them at Beatty. I did not have sufficient teachers to oblige. However, when I mentioned this to the senior teachers, Roy Jansen and Mrs Sheridan-Lee, they graciously volunteered to use their free periods to help those pupils. I had further support from Mrs Hollis-Bee and Chan Kai Yau. Thus, Beatty started to have a Pre U class.

The atmosphere was so congenial that Chan Kai Yau, (who later became Director of Education), was so pleased and willing to teach at Beatty that he declined an offer as lecturer at the Teachers’ Training College. He wanted more experience as a teacher. He was transferred only after I had gone to the Ministry. However, not by me!

Promotion to a higher grade.

A few months later, the authorities appointed me as acting Deputy Secretary B, Grade F, at the Ministry of Education, and later confirmed me in that post. With this promotion, I leapfrogged over Soo Ban Hoe who received an acting position in G grade as Senior Inspector of Schools. I suspected that some Honours graduates were annoyed they had not received promotions in contrast to some of us who did not have an Honours degree, but did receive promotions. Although they had proved their academic abilities, they had not done anything for the betterment of the service. I was pleased that the authorities recognised the dedication by some of us who restored Raffles Institution to its rightful stature. Furthermore, I was glad that I had kept my cool and dealt calmly, fairly and firmly with the rebel graduates who made trouble for me when I was acting Principal. The authorities obviously approved of my tactics.

Introduction to life in the Ministry of Education (Nov 1955 – Dec 1957)

In November 1955, Ince, who was Deputy Secretary in the Ministry of Education, sent me an informal note requesting me to come to the Ministry to act as Deputy Secretary B, Grade F. In earlier days, I had been ambitious for a promotion – not for status, but for a wider scope for implementing my ideas about education. Now, I preferred to stay at Beatty where I was fully appreciated and content. Several disincentives existed in the Ministry. The Permanent Secretary, Lee Siow Mong and I were not the best of friends. I, together with Paul Abisheganaden, had successfully moved a vote of censure on him when he was President of Stamford Club. I thought the Director, McLellan, was still imperialistic and paid lip service to David Marshall’s drive for Malayanisation. Furthermore, some Honours Graduates had not weaned themselves from their belief that academic qualification should be the sole criteria for advancement in the Service, although they took no initiative to appeal for it. However, I realised that if I declined the call to move to the Ministry, I would be contradicting the basic principles I had expounded to the Malayanisation Commission. I would appear to be afraid of accepting managerial responsibilities. I decided that I had to take the risk.

Ince who was Deputy Secretary ‘A’, had cordial feelings for me, but the tone of the memo he sent, made me feel that I was not really welcome at the headquarters and that I should not expect to be confirmed in that post. Possibly, he was under instructions from higher up. I quote his memo.

“To Mr V. Ambiavagar,

Principal, Beatty School. 4.11.55

Owing to the very great pressure of work that is now falling on the Permanent Secretary, it has been decided to call upon you for assistance with the administrative work at Headquarters.

Arrangements have therefore been made for your posting to act as Deputy Secretary ‘B’ w.e.f. 8.11.55.

Will you please hand over the school to Mr. Lim Hock Tian who is posted to act as Principal, Beatty School from the same date.

signed R.E.Ince

Deputy Secretary ‘A’“

I did not believe his rationale about the pressures of work. There were other reasons for my transfer. The post the authorities offered me, dealt with administrative matters in contrast to the post of Senior Inspector that dealt with educational issues. I was unfamiliar with administrative issues since I had not risen through the ranks of the civil service. I speculated that they used a manoeuvre intended to put me in a position where I would fail. Perhaps this would prove that a local teacher could not be a manager, and the principles I had propounded to the Malayanisation Commission were nonsensical.

Bleak beginnings

A room with a door labelled “Deputy Secretary B”, a table, a chair, a phone and two trays was my proud domain. No one told me my duties; neither did they give me a copy of the General Orders or a chart of the office personnel, nor any hint of administrative procedures. As soon as I sat down and looked at the walls, a peon arrived loaded with a mountain of files, deposited them partly in one tray and partly on the table and withdrew with a smile. Assuming that my work was in the files, I looked into them but realised they needed only clerical attention. Like a player on a field before a game started, I did a warm up for real responsibility by doing clerical work. I suspected that someone wanted me to flounder under the weight of clerical work, thus proving that local teachers were not fit for promotion under the Singapore Education Scheme and Malayanisation. Furthermore, I had a notorious reputation as a rebel against injustice. Perhaps the powers-that-be expected me to lose my temper. This would give them justification to condemn me for not being able to act tactfully. I decided to disappoint any such expectations.

Unexpected help

Patrick Purcell did not know me personally, but had a sense of fair play towards Asians. He sensed my situation, and dropped in to say “Hello”. When he saw the piles of files, he carried away most of them to delegate to the clerical staff or deal with them himself. He did that every day until only the relevant files came to me. From these files, I surmised that my main responsibilities were to manage the school buildings, furniture, grant-in-aid to mission schools and the budget. I obtained a copy of the General Orders and the organisational of the Ministry divisions and names of the chief clerks in them. Through careful study of several files, I got a hang of procedures and writing tactful minutes.

A glimmer of understanding

I dealt with the demands from schools, and disbursements for items approved by Government on recommendations made by the Ministry of Finance. The management of school buildings and equipment was a wider scope. It included the siting of the new Primary and Secondary schools. I coordinated with the Public Works Department to decide what could go into the buildings within the provisions of the approved budget.

Dealing with an unforeseen challenge

The implementation of the five and 10-year building programme led to the transfer of many classes and admission of new pupils in Primary schools. It required a high degree of tact and calmness in dealing with parents, guardians, politicians and Ministers of Government.

Within three weeks of taking up my appointment, I started getting requests for transfers and complaints from parents who came on their own or were referred by officials in other Government Departments including the Chief Minister’s office. Such appointments were very lengthy and kept me tied up from 7.30 AM until 8 P.M. I had absolutely no time for anything else. Each day, I went home for dinner and returned by 9 P.M. to work tirelessly through the files. I had to deal with Primary and Secondary schools admissions, requests for transfers and complaints about these issues. The Chief Inspector, Senior Inspector and an army of Inspectors of English Schools and the Supervisor of Primary Schools thought I should deal with this thorny issue! I had no authority to ask why I should be the official to handle it. I spoke to the Minister and suggested distributing the work among several officials. He agreed, but McLellan disagreed, saying previously only one official had dealt with it. He disregarded the fact that previously, this Ministry was only a Department of the Colonial Government, did not have an elected representative, and ignored most complaints. I suspected that he wanted to pressure me and literally break my back. I resorted to observing office hours and returning to the office at 6pm to deal with the files. I waited for McLellan to reprimand me so I could give him a piece of my mind, but he did not speak to me.

I solve an irritating issue

My experience in R.I. stood me in good stead in resolving practical problems that had a huge impact on the function of schools. One example was the timing of transfer of teachers. The Ministry usually handled such transfers after schools began their school year, thus causing disruption to teaching. Freshly-transferred teachers had to prepare new lessons. Officials in the Ministry claimed that insufficient clerical staff made it impossible for them to do timely transfers. I felt this was a lame excuse, and that the officials did not think or plan. Officially, this issue was not within my purview. However, I discussed it with the officer in charge, and instructed the clerical staff to carry out a simple survey that outlined the number of clerks needed and when they would be required. Thus in December, we worked out all transfers and implemented them long before January 1956. This enabled Principals to assign teachers to classes and specialists for the various subjects in secondary schools. Teaching in every class and in every subject could commence on the very first school day.

Mastering budget planning

Teaching in schools does not include experience in drawing up a budget even for a school. I had absolutely no training or experience in drawing up a budget for an entire Ministry. However, I soon realised it merely required common sense. For example, studying the files, I was amused to note that my immediate predecessors arbitrarily requested 10 or 20 per cent increases in clerical staff and unsubstantiated sums of money for projects, and the Finance Ministry approved only a small fraction of the requests! Both parties made arbitrary decisions regarding allocations. As a result, the Education Ministry responded by making internal adjustments for its own convenience. For example, the usual practice was that the Ministry requested clerks for its own headquarters as well as for schools. The school quota was one per school. If the Finance ministry allocated fewer than the total number requested, the headquarters retained some of the clerks intended for schools. This resulted in several schools not receiving any clerk and using teachers to do clerical work at the expense of teaching.

I enjoyed dealing with this challenge and quickly mobilised support. George Bogaars, the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Finance, had been one of my students at tutorials at Raffles College. I asked his advice and he sent Bolton, a staffing expert, to assess the number of clerks and other officials we should have. Since he was from the Finance Ministry, his report resulted in Finance approving our request for clerks. The problem of “borrowing clerks” from schools was resolved. He also helped further by writing to my Director about staffing and discouraged diverting clerks from schools to the headquarters. The downside of this was that some Asian senior officers accused me of currying favour with expatriates to get a promotion.

Broadening the pool who gained managerial experience

Four months into my stint at the Ministry, I requested permission to return to my substantive appointment as Principal, while the Ministry gave another Asian the chance to show his administrative abilities, and readiness for Malayanisation. The Ministry refused. Instead, they suggested I invite secondary school headmasters, on a voluntary basis, to help me on a part time basis and thus learn administration. Incidentally, it would help discover graduates, both Honours and Pass, who were potential administrators.

My first choice was Philip Liau, who had a Class Two Honours in English. I thought his writing ability would be a great asset. However, the experiment ended in frustration for both of us. I expected him to lighten my workload, while he expected me to train him! My next choice was Thong Sing Ching who proved to be commendable and the Ministry appointed him full time to act as Advisor on Text Books. With advice from members of the Graduate Teachers’ Association, he compiled detailed syllabi for secondary schools. After that, McLellan and Ince took over the task of selecting people for acting appointments. This pleased me, since I did not want to be accused of favouritism if I called in friends who were not Honours graduates but had administrative capabilities.

Issues in building new schools

One of my main responsibilities was to liaise with the Public Works Department for building new schools. I mapped the proposed locations and viewed them critically. Some schools were far too remote from centres of population. Subsequently, I visited some of the recently-built schools and noted that some had poor building orientation, with the sun blazing straight into classrooms. I discussed this with my superior officer, and brought up these issues with the Chief Architect at the Public Works Department. He agreed to deal with this issue. Another issue arose when the political opposition at that time (the People’s Action Party) objected to the high expenditure on school buildings. The Ministry of Education received instructions to cut down the budget on this item. I had the unpleasant task of proposing means of economy, which resulted in some primary schools being built without halls and their class room walls being shortened, thus having noise pollution that interfered with teaching.

Hock Lee Bus strike 1955 triggered a change in Chinese schools

The Hock Lee Bus strike was a watermark in the progress of Singapore. It began as a trade union action by workers in the bus company, but escalated when militant leaders and students from Chinese Middle Schools joined the protest march. Sadly, this ended in violent riots, leading to a few deaths, several injuries and damage to property. Curfew was necessary to restore law and order.

In the aftermath, the Government closed all Chinese Middle Schools. At the Ministry, we drew up rules including an age limit for all classes in school. This was to prevent Communist leaders who were adults, well beyond school age, from returning to the schools. They countered this by blocking entry to the Chinese Middle schools and preventing the reopening of the schools.

In 1956, a few new school buildings were ready for opening. I suggested making one of them available for the Government to introduce government-funded Chinese education. The Government accepted my suggestion. A large number of Chinese school pupils rushed in to register. Chinese schoolteachers responded enthusiastically to advertisements for recruitment. That was the beginning of an increasing number of Government-funded Chinese schools at both primary and secondary levels. The deadlock in the reopening of the private Chinese schools was broken. They realised that they had to accept the ruling to keep out over-aged pupils to prevent all Chinese schools coming under direct Government control. They also feared that the curriculum in the Government-funded schools would have increasing amounts of English language and this would result in the decline of Chinese culture. This scuppered the plans of Communist infiltration into Chinese education. Furthermore, when the Marshall Government took responsibility for the Chinese medium schools, it resulted in raising both the standard of education and the discipline in Chinese schools.

Non-functional staff.

I noticed two expatriate officials occupying high-level “super-scale” posts were non-functional. One was an alcoholic who took frequent leaves of absence. The other was Director of Technical Education. He neglected to distribute equipment donated by UNESCO, and left it in two rooms in the Singapore Trade School, thus reducing the space and equipment available for technical education. Risking his ire, I pointed this out to the Director of Education Mr. McLellan, and asked why this official received a salary to reduce the opportunity for technical education. He knew I would draw Chief Minister Marshall’s attention to the situation, so he agreed to act. Both culprits went on leave and never returned. However, McLellan used another weapon against me. I felt he made no move to confirm me and two other Asians, (Soo Ban Hoe and DaCosta) in our posts.

Promotion to Superscale F: A major milestone in my career

DaCosta took the initiative to deal with the situation. He drafted a memo on behalf of all three of us enquiring why our confirmation was delayed whereas that of expats had been completed. At his request, the three of us signed, with my name first since I was the most senior. The Director, in his reply, claimed that there had been equally long delays in the appointment of the expatriates. DaCosta drafted a second minute in which he provided evidence that the expats had indeed been confirmed without delay.

McLellan knew that I had good rapport with the Governor of Singapore, Sir John Nicoll and the Chief Minister David Marshall. Therefore, I suspect he tried a manoeuvre within his level. He called a meeting with the William Goode, Chief Secretary to the Government, and officials of the Graduate Teacher’s Association (GTA). He knew Goode did not look upon me with favour because I had gone over his head to the see the Governor, on the issue of the Singapore Education Scheme. He used the meeting to try to browbeat the Association officials. However, the president of GTA, Yapp Thean Chye, stood his ground. The minutes of the meeting stated the Chief Secretary gave a warning to the Graduate Teachers’ Association in general, and the president Yapp in particular, stating that “the President especially had put himself in grave peril as a serving officer in the Civil Service.” Yapp asserted that he had acted as president of a trade union not as a civil servant. The Minutes recorded McClellan as saying, “a decision would soon be made in three of the four posts in question.” Obviously, they planned to make rapid moves on the promotions to prevent us taking up the matter with the Chief Minister or the Governor.

Soon after, I received the official letter that not only confirmed my appointment but also backdated it for 14 months although I had done only 10 months of work in that post. I include an exact quote of the official letter to illustrate how different it is from the initial casual note the Ministry sent to me when they asked me to move there.

A letter from the Chief Secretary’s office dated 11th September 1956, signed by a junior official, on behalf of the Chief Secretary, came to me through the Director of Education informing me:

“I have the honour to inform you that the Secretary of State has been pleased to approve your promotion to the post of Deputy Secretary, Grade F, Ministry of Education, with effect from 21st July, 1955.”

I have the honour to be,

Sir,

Your obedient servant,

J.A.R. Macdonald

For

Chief Secretary, Singapore.”

I put on record here that Yapp Thean Chye was a very sincere and loyal friend who was always ready to give support to his leader irrespective of consequences.

An example of my previous encounter with Goode, when he was Chief Secretary illustrates our less than cordial relationship. He invited me as the President of Graduate Teachers’ Association to discuss the proposed Education Scheme. One of his frivolous questions was, “Why do we have so many classes and so many teachers? Would it not be economical to have halls instead of class rooms and large classes with fewer teachers?”

In response I asked, “Why have schools at all? It would be very economical to give lessons over the radio for pupils in their homes.”

He laughed it off but I could sense that he was offended at my irreverence.

My Promotion

PROMOTION ON MERIT

The promotion had tremendous significance for me. Customarily, promotion was based on length of service and paper qualifications. Outstanding ability, irrespective of length of service, received no recognition.

This promotion set a precedent because I was the second example (after Balhetchet) of gaining promotion over me.

The promotions of Balhetchet to G grade and three of us to Superscale administrative grades was a historical event in Singapore Education for it marked the beginning of the transfer of administrative control of education services from the United Kingdom to Singapore.

I had mixed feelings on getting the promotion to ‘F’ grade. It was a triumph over formidable opposition. I was very happy that Sir John Nicoll was Governor and probably decided on my promotion; and I was pleased that David Marshall was the Chief Minister whose drive for Malayanisation influenced my initial upward progress. I was proud that Yapp Thean Chye was a ‘tartar’ who refused to be intimidated. In addition, I was amused that I was getting 14 months promotion for my 10 months’ work. I would have been happier if I had received confirmation as Principal Raffles Institution. That would have allowed me to greater scope to implement my own ideas. I greatly valued the congratulation from Prof. E.H.G. Dhobby, Dean, Faculty of Arts, University of Malaya.

“Dear Ambiavagar,

I have seen that you are now appointed to be a Deputy Secretary and I would like to extend my congratulations on the promotion that this implies. It clearly represents the most senior appointment in the educational world which any Raffles College or University of Malaya graduate has yet attained.

I hope your interest in the University graduates will be continually brought into play and that we can depend on you to foster the advance of University education and of the University man in this territory. We shall need in the next couple of years every bit of support in maintaining the machinery and the production of the University of Malaya at that pitch which the country needs and the standards we have been maintaining.

It is not enough for us to turn out graduates. We must look to graduates to be consistently advertising the importance of graduation.

With my best wishes for your new future,

Yours Sincerely

Signed E.H.G. Dobby 15/9/’56.”

I also had a congratulatory note from Jesudason:

“Dear Ambi,

I was very pleased this morning to read in the Government Gazette your confirmation as Deputy Secretary!

We at Bartley are very happy to hear of your promotion.

All the best.

Signed E.W. Jesudason. 16/9/56.”

I learn how things work in administrative circles!

One day, I was very surprised, when Dr. Ho Seng Ong, my former teacher at the Methodist Boys’ School, now a member of the Public Services Commission, visited my office. I had never been his favourite pupil. He did not congratulate me on my promotion. I wondered why he visited. I became cagey and apprehensive when he asked me about various members of the staff at the Ministry.

Later, Lee Siow Mong (Permanent Secretary Education, 1957-59) cheekily asked me if I had used Seng Ong to get my promotion confirmed. I reminded him that I had not visited Seng Ong – but he had visited me to fish for information about my staff. I had told him all of them were good.

I fall foul of Chew Swee Kee, Education Minister.

Following a briefing by the Minister of Education, Chew Swee Kee, I drew up a set of rules governing admission of non-resident pupils. Late in 1957, he sent me an Indonesian boy and his father and told me over the phone to admit him. The boy did not fulfil the conditions laid down by the Minister himself. Therefore, I sent him the file asking him to confirm his phone instruction. He picked up the phone and asked angrily why I did not act on his phone message and wanted him to confirm it in the file. I told him that I was following standard administrative procedure to indicate that I was giving an admission on Ministerial orders, contrary to the approved rules. He cursed, but confirmed his directive.

I remembered at that time having read a philosophical pronouncement that a wise person has to be adaptable for survival. However, I also felt sorry for people in corrupt countries who had to survive on that kind of wisdom. My family had survived the Japanese Occupation because I accepted Japanese rule and did not join those who had gone underground. I did not want to survive as a Deputy Secretary. My survival in the education service was more important.

I was not surprised when Lee Siow Mong told me, early in December 1957, that, on instruction from the Minister he was transferring me to Raffles Institution as Principal.

My superiors in the Ministry viewed that I was “kicked down” from the Ministry, deprived of the ‘privilege’ of being a high-level civil servant. Personally, I did not feel it was a “kick”. I was pleased to escape from a trap in which others could make me look guilty for all sorts of reasons. I was genuinely relieved at not having to work under a Minister, a Permanent Secretary and a Director who were hostile to me, and delighted to escape the very long hours of work without any time for recreation.

First Asian Principal of Raffles Institution: December 1957-April 1959

Back home again!

I was back at my ‘home from home’.

The place had given me sheer happiness for more than 20 years.

I certainly did not anticipate that later on, in my retirement, I would be repeatedly honoured as the first Asian Principal of Raffles!

On the first day that I arrived at the school, in December 1957, the Head Prefect and a few others showed me a letter of resignation by the full body of prefects. They had intended to give it to the Acting Principal who I displaced. Their complaint was that he would not take any disciplinary action against pupils who broke school rules. They did not want to be the laughing stock of troublemakers. I promised to back them but advised them not to retaliate if any pupil laid hands on them but let me deal with him. It surprised me that the school that had progressed with good discipline under Young had lost that quality in eight months under an Acting Principal.

I issued a circular on disciplinary conduct making it clear that I would take action against pupils who disobeyed school regulations. I specified that everyone should obey school prefects and they should bring any complaints against a prefect to me. Very soon, a pre University pupil punched a prefect when told not to break the queue in the canteen. I called him and his father, and told the father what his son had done. Before I could go further, the father made his son bend over my table and caned him! He thanked me for letting him deal with his son. In later days, that boy graduated from the University and whenever he saw me at a function, he would greet and speak to me, showing appreciation for the way I had dealt with him. Correcting just one case of indiscipline brought the school back to normal and there was no more trouble.

Regretful to forego the opportunity to bag a Champion Athlete.

Mr Vasagam, the former Malaysian athlete who held for many years the 440 yards record, came from Kuala Lumpur to ask for a place in R.I. for his son Jegathesan who himself was a budding international athlete. I was sad, but had to tell Mr. Vasagam the rules that prevented my admitting Jegathesan because he was not a Singapore citizen. I suggested he approach the Principal of A.C.S. who had such a strong political standing that he could probably ignore the Ministry ruling. Jegathesan brought much fame as an athlete to A.C.S. and eventually fame to Malaya and honour for himself as a doctor. The father took my refusal in the right spirit and became a good friend.

New staff but well geared for action. Preparing for the future.

More than 50% of the staff who had been in R.I during my previous sojourn had left, on promotion or transfer. The new staff had to makea quick adjustment to my style of management. They did know how I felt about discipline and dedication to teaching. Furthermore, they had both experiences of working under principals who adhered to these ideals and those who did not.

Through discussions with the departmental heads and supervisory rounds, I soon reached the conclusion that every teacher was committed; many were dedicated and a reasonable number were going the extra mile. R.I. had not lost its identity despite the loss of experienced teachers. Extramural activities were in full swing, and the progress in athletics under Pestana and gymnastics was impressive.

Every day was a joy for me. It was like being on a long vacation. I introduced only a few changes.

I anticipated an increased emphasis on the teaching of Chinese, Malay and Tamil in the near future. It was long overdue. The 10-Year Plan approved by the Governor-in- Council in August 1947 included a resolution to start teaching these languages in Government and Grant-in-Aid Schools. However, the authorities ignored that resolution. In fact, the concept of fostering civic loyalty and responsibility, building interracial understanding and collaboration through education continued to be neglected.

I had difficulty getting teachers for the languages. The available Chinese language teachers had poor teaching techniques, and made the language terribly boring. I managed to obtain the services of a retired Tamil teacher, and improvised for Malay by offering a few students who were proficient in the language the opportunity to teach classes. Thus, when the PAP government enforced the teaching of vernacular languages in 1960, Raffles Institution was ahead of the other schools by two years.

Inserted by the editor:

“He insisted on extreme efficiency, exemplary conduct, hard work,. punctuality and serious devotion to duty. This attitude pervaded the entire school ….. the school was in tip-top shape. (The boys) had the greatest regard for him ….. They showed this when he visited the school as acting deputy director of education on the school’s Founder’s Day celebration in 1960. As he ascended the stage, the boys commenced a thunderous applause that could not be calmed, except by Ambiavagar himself. He was visibly moved.

Excerpts from The Eagle Breeds a Gryphon by Eugene Wijesingha.

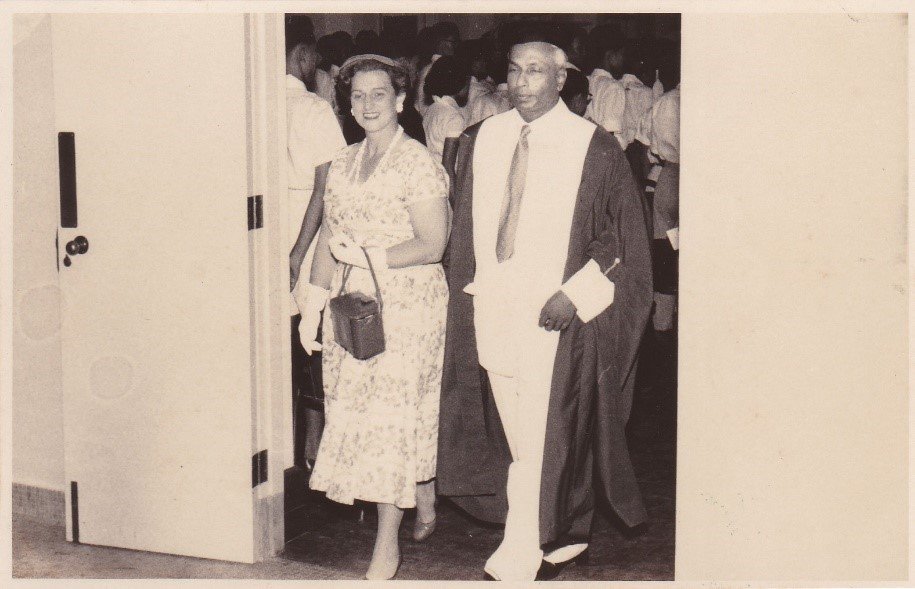

Ambiavagar and Mrs McLellan at the school function.

An unexpected promotion and move back to the Ministry.

I was surprised in 1959, the same officials who sent me out of the Ministry, hauled me back as Acting Deputy Secretary/Deputy Director A, on a higher post, namely Grade E and requested me to name an Acting Principal for R.I.

I had difficulty deciding whether to nominate my friend Philip Liau or another officer Seah Yun Khong, since both had good justifications. I consulted the senior official at the Ministry and he suggested I nominate both and let the Public Services Commission decide. The PSC decided in favour of Seah, and I am afraid I lost the goodwill of Philip, although I explained the process to both of them. I am sorry that Philip displayed his bitterness in the inaccurate statements about me when he wrote in a Souvenir magazine (1973) of the history of Raffles Institution. He completely omitted any mention of the period when I was acting principal and the contributions that I made, and gave inaccurate information of the work I did in the Ministry. This publication hurt my feelings deeply.

The PAP won a landslide victory in the election in 1959.

My old adversary the Minister Chew Swee Kee was impeached and left the Singapore scene.

Within the PAP, serious conflicts raged between the socialist leaning wing under Lee Kuan Yew and the communist leaning wing led by Lim Chin Siong — which had strong ties with communist China. Similar tensions existed in the Chinese population of Singapore. Lee Kuan Yew had his hands full overcoming the opposition within his party and consolidating his support from the population.

He appointed Yong Nyuk Lin as Minister of Education. Yong, who was married to the sister of Mrs Lee Kuan Yew, and supported Lee ardently.

In April 1959, I participated in a discussion on radio about the Singapore Education Policy. The others in the discussion were David Marshall and G.G Thompson. Subsequently, Howitt who had retired, sent me a congratulatory note that illustrates the fundamental issues that occupied my mind at that time.

Excepts from the Letter from Howitt, retired Principal of Raffles Institution

Dear Ambiavagar,

I listened to the broadcast this evening and heard you “under fire” in defence of the Education Policy.

I thought you were admirable and most restrained when you could have replied with asperity to the criticism of present policy and achievements. As you said “Rome was not built in a day” – and in the long run Educational Policy must always follow demand – e.g. when Singapore is industrialised we shall build trade schools enough to supply the technical workers … (and) supply of Legislators and Administrators .. to run the state as it wishes to be run.

The point that loose thinkers miss is that Secondary and even University education is still only a training in the way to use one’s brains for a full and efficient career. It is only after an all-round start in many fields of training, Arts, Maths, Physics, and Athletics, that a man should specialise and develop his talent without losing sight of other important values. Our secondary schools are doing very well (I cannot speak for Chinese secondary schools) and from the last R.I. results in the in the S.C. and P.S.C. we have little criticism to fear about the quality of our teaching when judged by world standards.

In regard to multilingualism, the critics on its behalf lose sight of the strain that is placed on a boy who has to learn several languages before he is eighteen years old, and fit for a university course. He will naturally concentrate on the one most likely to prove useful. You can’t take one Chinese, one Indian, one Malay, all at the age of six, give them a 11 year course of National Education and expect them to turn out true Malayans… It will take some generations of social intermixture and racial inter marriage.

Patriotism is comparatively easy to inculcate. Any battle cry in defence of the home, or in Dictator States, aggression will suffice as a way to glory for the rulers. However, it will take a century or more before we get a truly Malayan nation. There is, it seems, no reason why these races should not live in harmony all the while. They have done so throughout Malayan history, as far as I know, with only rare sporadic, purely local riots, or vendettas. New born patriotism, and enthusiasm for local culture shouldn’t be allowed to stand in the way of what we call ”progress” As far as I know, English and the wide secondary school course gives our children and pupils the best back ground for taking up life in harmony with the modern world.

I am sorry to prose on like this, far into the night, but I was stirred and delighted to hear you speak so well in defence of what is being done for students in Singapore by your department. Peter Wilson in his grave would be pleased, as would other old headmasters of R.I. through the decades. Their only wish was to give pupils the joys of knowledge and judgement; and turn out loyal Singaporeans or Malayans well equipped to be successful in their careers and to contribute to the good of Singapore.

I am glad to see you back in your old job, Ambi. I hope it is only a stepping-stone!

My regards to Mrs Ambiavagar.

P.F. Howitt

Acting Permanent Secretary/Director of Education April 1959- 1961

Some might view my return to the Ministry to a top position as the pinnacle of my career. For me it was a highly stressful and professionally unhappy period.

I had two major challenges.

I had fundamental differences in opinion with the Minister Yong Nyuk Lin on the best approaches to adapt the Singapore education system to the aspirations of the new nation. While we agreed on the need to address the barriers due to separate educational streams in English, Chinese, Malay and Tamil, we had differing views on how best to resolve this. In my view, he had a shallow understanding of education and recent educational and cultural history and the evolving societal changes in Singapore. I felt He tended towards a narrow populist approach.

More importantly, I was very uncomfortable with his managerial style. Unlike other PAP leaders such as Lee Kuan Yew, he excluded professional input in policy decisions, and tried to impose narrow political considerations to the exclusion of educational principles. In this atmosphere two highly experienced and valuable top officials – Lee Siow Mong, a well-respected Chinese scholar and Hoffman, a very senior civil servant Left the Education service. Their responsibilities descended on my shoulders. The Minister gave credence to anonymous letters of complaints containing unsubstantiated allegations and supported investigations of such complaints, thereby generating much unhappiness and discontent among teachers and principals. Many of them blamed me for such actions. In fact, there was an anonymous letter about me as well, which alleged that I had not taken disciplinary action against a Principal described as my personal friend but whom I didn’t even know! Although he bypassed other officials to rely on me to draft his cabinet papers and implement his decisions, he simultaneously told me that the Chinese language press did not like me. I surmised this was because I had given evidence that helped convict the Chinese Middle School students who attacked the police during their protest march in 1953.

I felt he clearly resented the occasions when I expressed opinions contrary to his, or contradicted him when an instruction he gave was not suitable or pragmatic. In order to adapt to his style, I tried to adapt, by postponing action on issues on which I disagreed with him. I hoped that he would forget about them.

Contrary to my expectations, Yong must have been satisfied with my performance because he recommended my confirmation as Deputy Secretary A, Grade E, and later, he wanted me to take on the role of Acting Permanent Secretary/ Director of Education when Lee Siow Mong and Hoffman left. I was foolish in feeling flattered and thinking that I could cope. I should have realised that I would not be able to manage the work done by two experienced civil servants, particularly since I did not have a competent Deputy. In addition, this occurred at a time when the government introduced a slew of new policies. I should have refused this so called ‘honour’!

Furthermore, I should have paid attention when Yong told me a couple of times that the Chinese press queried how a non-Chinese in the position of Director could advise him on Chinese education. At about the same time I received a bullet through the post. No one recognised that I had introduced without fanfare several key measures to support Chinese language education. Examples are the opening up of government-funded Chinese schools, and the employment of Chinese language teachers in Raffles Institution two years before it became official policy.

In my opinion, Yong introduced communal bias and prejudice in the Education Service in Singapore.

Financial pressures

I had an additional challenge of financial stress. The government cancelled Pensionable Allowances of all government employees, resulting in a monthly reduction of $700 from the joint incomes of my wife and me. Meanwhile, we had mortgage loans to pay on our property. I requested permission to retire so that I could use my gratuity to settle a mortgage loan and invest the balance on a property, but Yong persuaded me to withdraw my application. I did so reluctantly, because I did not want to offend him.

The final straw precipitated early retirement

Despite everything, I thought he was satisfied with my work. However, the final straw came soon after. He used foul language to express his anger because I had failed to persuade the University Council to accept a certain policy with regard to admission to the University. I decided immediately to request permission for premature retirement. I told him frankly, why I was asking for it but he wanted me to delete my reason. I agreed thinking it would end our relationship on an amicable note. However, it did not. In subsequent years, Yong referred to it as a friendly act by him and that I was ungrateful to him!

In fact, even after the Prime Minister had agreed to let me retire, the Minister tried, in vain, to provoke me, for nearly an hour, to lose my temper, and respond angrily. I felt he did this so that he could charge me with insubordination and thus deprive me of my pension.

The dreaded Minister!

Yong Nyuk Lin, Kiang Aik Kim, Low Kee Pow, Ambiavagar and Wee Siong Kang.

June 1960.

I have reason to believe the Government was pleased with me. It did not object to my appointment as a special lecturer at the University, for which I received a handsome salary. In addition, there was no opposition to my appointment as a member of the Liquor Licencing Board. Moreover, later, when I wrote to the Prime Minister stating my counter views on his proposal to establish elite schools he did not slap me down but instead, thanked me for my letter.

In retrospect

When I think back, I feel that my decision to retire was part of my life pattern of impetuous decisions and actions. I had not planned it nor had I thought about what I was going to do after retirement. Strong emotions that mounted up within a few days, suddenly reached a climax that led to my action.

Far from regretting my premature retirement and despite unforeseen difficulties that cropped up, I was certain I had done the right thing. My retirement allowed us to settle our mortgages, and indulge in a large wedding reception for my daughter, as was expected in our community at that time.

My surprise retirement was not altogether a surprise for my friends who knew me intimately; several dropped in on me. Frank James who had worked with me closely since our reviving the Singapore Teachers’ Association wrote me the following letter:

9 Capitol Flats

Stamford Road

Singapore 6

13. 7. ’61.

Dear Ambi,

Please allow me to use the affectionate Nickname by which I have always known you.

The news in today’s Times was sad, because you have resigned before your time, and because I feel sure you worked very hard all along on the lines of your ideals. (Not resigned but retired.)

Few Aided School teachers have had longer and close association with you.

We did our combined best for the S.T.A. and turned it into the S.T.U.

You must have been born great, acquired greatness and then had greatness thrust upon you, all in the space of one lifetime.

Thank you for your friendship and God love you for it. I am glad to have known your dear wife too.

Believe me, please, when I say that I regret your premature withdrawal from the scene of our past united, and present separate, efforts but you must know best.

You and your good wife will be remembered with fondness in our prayers and thoughts always.

On behalf of those teachers who know you best, I say a very big THANK YOU for what you have striven to do for us, and I wish you a VERY HAPPY RETIREMENT.

Yours, for years too many to be counted.

Yours Sincerely,

Frank & Iris C. James