The emerging new State of Singapore provided a dynamic backdrop to my life. Three parallel threads characterised my life. Firstly, my family and I adjusted to the evolving circumstances of life in Singapore. Secondly, I became deeply involved in rehabilitating and re-establishing Raffles Institution to its rightful role as a premier school. Thirdly and finally, I campaigned successfully for parity in recognition and benefits for Asian teachers. All of these threads or events were interlinked and therefore influenced each other.

For ease of reading, the next three chapters recount the events of each thread separately.

Adjustment to fluid living conditions in post-war Singapore.

Immediately after the Japanese surrender, I returned by cab to Singapore (with Seow Cheng Joon), to arrange accommodation for my family and report to the authorities for work. The journey was long and slow. We negotiated rickety wooden bridges built by the Japanese to replace those blown up by the retreating British during the Japanese invasion in 1942. In addition, we experienced long delays at the sentry posts set up by the British forces for searches of vehicles and passengers.

On arriving in Singapore, I learnt that British soldiers had occupied our quarters[1] in Haig Road, as well as our own house in Goodman Road. Ponniah, our old time friend, generously offered us accommodation in his quarters in Penang Road, despite having a large family of his own. I reported for work, but it would take a few weeks for the authorities to reorganise the system and reopen schools. Therefore, I returned to Kuala Lumpur to sell the cows and poultry, arrange for the care of the house and plan the return journey with my family.

After an initial stay with the Ponniahs, we soon moved to the neighbouring house of Arumugam who was a widower who lived with one teenage daughter. Somu was still with us, and we also had help from a young girl who worked as a baby sitter. Our host and we were very comfortable with each other. We provided domestic care and cooking. I even commenced giving private tuition to two pupils. However, this happy state of affairs ended when our host extended his hospitality to another family. This brought irritating minor conflicts. We could not afford to move into a hotel. The situation ended when the guest family left, having poached our baby sitter!

Early in 1946, the army returned our Haig Road quarters, although they retained our Goodman Road house. The Haig Road house was far too small for our family of four children with a fifth expected in the near future. The two bed rooms could take in only two small beds each. We allocated the front room to Mahendran and Indra, gave them each a bed and in the second room we devised a low wooden platform as a bed with straw mats for three children and ourselves. The “bed” filled the entire room leaving only a narrow walking space to the bathroom door. We bought a cheap table, a few chairs and a small refrigerator. When schools started to function, I managed to get Mahendran enrolled in Primary Five as a pupil of St. Joseph’s Institution, and Indra in Primary Three at Raffles Girls’ School.

Our cramped living quarters left us no choice but to move in with another friend who had more space in the larger Penang Road quarters. Our finances were low. I had no money for a car; public transport was scarce; vans and lorries were the means of public transportation. Mahendran, Indra and I commuted to school in a crowded van. Indra caught the whooping cough; all the other children were infected and we lost our 10-month old baby, Saras when her cough turned into broncho-pneumonia.

[1] “Quarters” is the term used for housing allocated by the government to its employees for a minimum rent. The quarters in Penang road were two storey linked houses, and very much more spacious than the Haig Road houses that were small semi detached units.

Rajen’s health 1946-47

Rajen’s health worried me. Pneumonia hit him just before the liberation when there were no antibiotics. Pneumonia was a deadly disease and we were terrified for him. However, he fought it off and gradually regained his strength. However, in 1946-7, when the other children caught whooping cough, he too came down with it and it became a threat to his life. He suffered frequent bouts of dysentery and fits. One day his fits were very severe, when Mangalam had gone to work and I was caring for him. I was desperate with fear. Since there were no telephones at that time, I sent young Indra by trishaw to the clinic of my old classmate and friend Dr. Hu Chee Ing, who now was our family doctor. He came immediately, attended on Rajen efficiently and I was reassured. Because of Rajen’s poor health, we did not send him to school until 1953 at aged 11 when he was placed age-appropriately in Standard 3. Mangalam had been teaching him at home. Unlike his elder siblings, he did not lose years of education because of the way years. Unfortunately, he did lose out on the supplementary education that comes with peer companionship and also missed sports activities and games. He became conscious of this handicap and set about resolutely to take remedial measures. Thus he gained admirable success in studies, in his profession, in health and in family life.

1947: Lovely Baby Sarab brought joy to the family but tragedy struck when she died 8 months old

1948: The Ambiavagar siblings

Rajendran, Mahendran, Indra and Leela

Mrs. Ambi home tutored her elder children so they did not lose school years

For the first time, we enjoyed our own house (1947-48)

In 1947, when our tenant in Goodman Road fell into arrears of rent for our redecorated and refurnished house, we evicted him and moved in. Our finances improved. My salary as a graduate teacher was only $300 per month. I added to it with $100 from private tutoring, $? as a part time lecturer at Raffles College and $175 as cost of living allowance. Also, it was fortunate that I collected ‘back pay’ of about $4000 for the Japanese occupation period, and compensation for my car that I lost to the Japanese.

In July 1948, teachers’ salaries were revised and back-dated to April 1947. That gave me arrears of $6748 and raised my monthly salary to $525, including my graduate allowance of $50. Thus my steady monthly income jumped from $300 to $725. I stopped giving tuition but kept my part-time job at the University. We expected to be able to afford the luxury of living in our own house and bought an Austin car. Mangalam also secured a teaching job at St Hilda’s School.

The Goodman Road house

We had a tennis court in the compound, and Ambi enjoyed playing tennis with his friends and Mahendran.

Excerpt from Mrs Ambiavagar’s autobiography

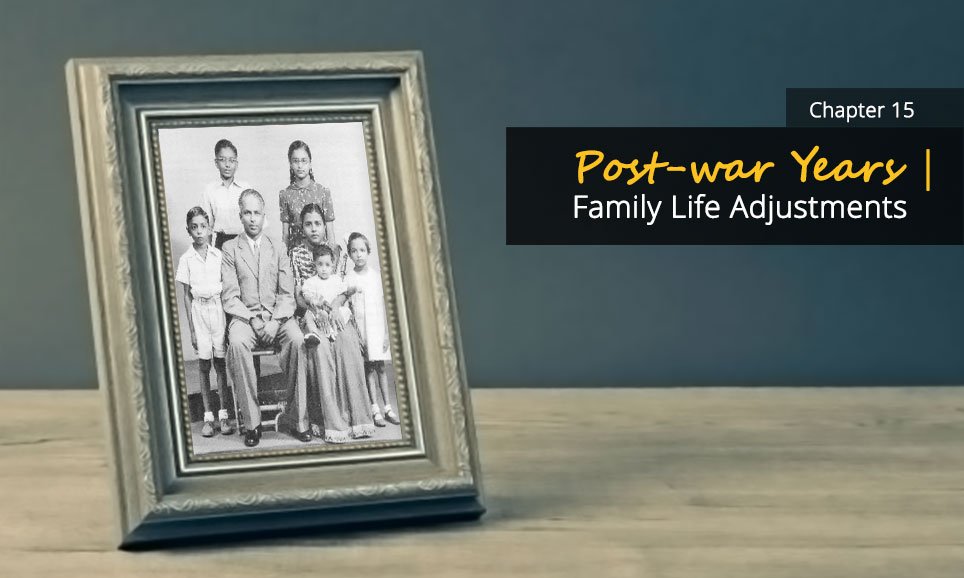

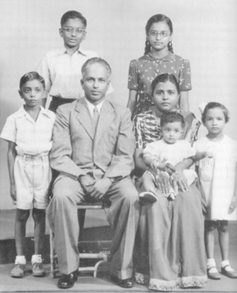

Our family was complete in 1948

Gnanam arrived in 1948, and her vivacious and loving personality went a long way towards healing the loss of Baby Sara two years earlier.

1951: Eve of departure to Ceylon

With the arrival of Gnanam, the family was complete.

Mahendran’s dilemma

Mahendran took his School Certificate Examination in 1951, and his results qualified him for admission to the University to study Medicine. However, he was underaged for admission in 1952, and would have to await the 1953 intake. Meanwhile, the University had announced without forewarning, that for admission to study medicine, beginning 1953, applicants would need to sit for Physics, Chemistry and Biology as separate subjects in the University Entrance Examination. However, secondary schools taught only General Science and were not prepared for the change. Students wishing to apply for Medicine would need to attend private tuition schools to prepare for the new subjects.

“Nothing that is worth the while is easy to get and we beg those who are responsible for shaping our future to spare no cost or trouble in providing us with Higher School Certificate (classes). Without it, we are desperate and the University is a terrifying institution.”

A.Mahendran, Standard IX A

The Rafflesian. Vol 24. 1950

We decide to send Mahendran to Ceylon to prepare for University admission.

We were concerned about the quality of pre-university education Mahendran would get in Singapore because schools were yet to organise their classes for the new entry requirements. Mahendran had made a holiday trip to Ceylon, and liked the idea of going to Colombo to study the required subjects for the Higher School Certificate and thus qualify for admission to the University. This would earn him exemption from the pre medical year, thus making the medical course five years instead of six. Therefore, we decided to send him to Colombo.

A momentous decision: relocating the family in Ceylon

During this period, Mangalam, casually expressed the wish to experience life in Ceylon. After the experiences during the war years, she wanted to return to a country that might be considered our ‘homeland’. I thought it would be a good idea to combine Mahendran’s stay in Colombo with Mangalam going there to satisfy her wish. I too had my own self-interest in that scheme. The then Director of Education has promised me a scholarship to study for the Honours degree at the University. I would be free of home chores and family cares and could concentrate on my studies. The other children would benefit by experiencing a different environment. Therefore, I suggested that Mangalam go to Colombo so she could care for Mahendran. We were uncertain of his ability to look after himself. She agreed readily, and went so far as to consider selling our properties, settling the mortgages and taking some of the capital to invest in Colombo. Already she was thinking of settling for good in Ceylon!

We shipped our furniture and car to Colombo, paid “key money” to rent a new two-storied bungalow in Buller’s Road, a prestigious area, set up home for the family and hired a chauffeur. I returned to Singapore, boarded for a while with the Ponniahs, then rented a room with the Karmakar family and commenced reading for my Honours course.

My family settled in. Mahendran gained admission to the Higher School Certificate class at St.Joseph’s College. Indra started in Form 4 at the Methodist Girls’ College in Colombo. Rajen and Leela continued home tutoring by their mother. In addition, a private tutor taught Tamil to all of them since it was a compulsory second language.

Mangalam bought a building lot and planned to build a house. She wrote suggesting I retire from teaching in Singapore, settle in Colombo and go into partnership in a printing business with my cousin, Amarasingam. However, during two visits to Ceylon, I strongly felt that the politics in the country was such that it would soon lead to an outbreak of civil war. Furthermore, I did not know Amarasingam well enough to go into partnership with him in an environment that was foreign me. Therefore, I refused to budge from Singapore.

Amarasingam kept in close contact with the family. He was an ardent communist and edited a leftist newspaper using a small printing press. He needed more capital. Mangalam wanted me to join this business. I was decidedly uncomfortable, but did go so far as to lend Amarasingam $12,000, which turned out to be a total loss. He never repaid the loan despite several promises.

I was glad I retained my job in Singapore and did not end up in bankruptcy!

My opportunity for an Honours Degree is scuttled.

After the fiasco of the Teachers’ Union (Chapter 17), I decided to study for an Honours degree at the University. As a part-time Lecturer I had kept up my reading. Professor Hough, in the University knew this and encouraged me to apply for admission. My ambition was to secure a Second Class Upper. Mr. R.M. Young, the Director of Education, granted me three months fully-paid leave in advance to read intensively and promised me full pay as well as my allowances during my University year.

During the same period, Mr. Young went on long leave. I assumed that he would have left a note that he had promised me full-pay study leave to do the Honours degree. However, another expatriate officer whom I did not know, replaced Young in an acting position. He reduced my promised full pay to half and instead surprisingly gave the privilege of full pay to Jesudason, although Mr. Young had previously rejected Jesudason’s application.

I was furious at such abrupt treatment. Impetuously, I rejected my University admission, returned to work, and obtained Government quarters for residence.

In retrospect, I feel that I did not lose anything by this decision. Perhaps the wrong decision was in wanting my family to experience life in Colombo. It made a significant dent in our material possessions, that later led to us being sunk in a mortgage, when the Government took away the pensionable allowances of all civil servants.

I recall Mangalam to Singapore.

My plans changed radically. I had scuttled my plan to study for Honours and now was eligible for good-sized government quarters. At the end of 1952, I persuaded Mangalam to return with the three younger children, leaving Mahendran and Indra to completetheir current school years in Colombo. We transferred the Buller’s road rented house to Amarasingam together with all the furniture and our piano. However, we sold the car at its original price, thus thankfully recovering some money. Mahendran lived with the Amarasingams, while Indra became a boarder at her College, and went to stay with them for weekends. We transmitted money for their fees as well as for their boarding.

We recall Mahendran.

Within a short time, we had reports that Indra was coping well with her life and studies but Mahendran was losing weight and looked like he might fall ill. By mid-1952, we had no choice but to call him back and put him into the pre-university class at Raffles Institution. Meanwhile, Rajen had started in Standard 3 at Monk’s Hill School and Leela in Standard 1 in Raffles Girls’ School.

Mahendran sat for and passed the University Entrance Examination in March 1953, and did well enough to win an Entrance Scholarship, and gain admission to Medical Faculty of the University in October 1953.

Indra returns

Indra passed her School Certificate Examination in Colombo and returned to Singapore at the end of 1952. In January 1953, she gained admission to the Pre-University class (four terms) at Raffles Institution. She had studied Physics, Chemistry and Biology in Colombo instead of General Science like her cohort of students in Singapore. This enabled her to be a rival of Hwang Peng Yuan for the top position in her class and she went on to win an Entrance Scholarship to study Medicine at the University in October 1954. I feel that her stay in Colombo and exposure to a wider life gave her not only immersion into the culture and value systems of our own community, but equipped her to cope with a variety of people. I believe that her success in life, working with distinction in the international arena including the World Bank owes much to such a valuable experience.

Witness in a controversial case

In 1954, in a first big political involvement, Chinese Middle School students marched to protest against the Government proposal to introduce National Service. The background was as follows. In 1949, the Colonial Government had piously approved a new Education Policy to inculcate national consciousness. However, they did not implement it. They knew that a vast majority of Singapore pupils were in private Chinese schools where communism was deeply prevalent. Instead, the government tried to introduce National Service in 1954. To my mind, the move was illogical. The hostile reaction of the Chinese schools’ was predictable and a crackdown by the police would only strengthen the independence movement that was already afoot.

I happened to have a grandstand view of the clash between the Police and Chinese school pupils. When the pupils marched to the Governor’s residence to protest against National Service, I heard an unusual noise in front of my house in Penang Road, which is en route to the Governor’s residence. Looking down from the first floor verandah of my house, I saw a police van parked right in front of my residence with a police contingent behind it. Next, a procession of Chinese school pupils appeared from the south singing in Chinese. The police van shouted orders in Chinese. The students did not heed the instructions. Instead they picked up broken bricks which had been piled up in front of houses undergoing minor repairs and threw them at the police. Protecting themselves with shields, the police charged at the students who retreated in disorder. The police pursued them and I lost sight of both.

One of my colleagues in school heard me mention that I had witnessed the clash and conveyed this to a police officer. Thus I was asked to be a police witness. If I had any political wisdom I should have excused myself from giving evidence by pretending that I had seen too little to give valuable evidence. At the court hearing I was the only witness for the police, and Alex Jocey, a journalist, was witness for the pupils. The police alleged that they had ordered the pupils to disperse or turn back but that the pupils had attacked them with bricks and stones. The students’ defence was that they had not thrown bricks and stones but the police had charged and hit them with batons. I testified to what I had seen and said I did not see the police hitting the students because when the police pursued them, they dispersed beyond my view. Alex Jocey testified saying that he had seen the police taking the initiative to hit the students with batons. On cross examination, I was confronted with this. I wasn’t playing politics but being factual. My answer was that I had seen Alex Jocey come on the scene from Penang Lane on the left, only after the pupils had thrown the bricks and the police were charging them. He could not have seen the commencement of the clash.

The pupils were found guilty. They appealed. Their lawyers, Mr. Lee Kuan Yew and Mr. Pritt Q.C. came to my residence to check what I could have viewed from my verandah. Mr. Lee told me later that they lost the appeal because they could not shake my evidence.