Japanese Invasion

World War II caught us by surprise.

Putting things in perspective and reflecting on history, it seems to me that World War I was a conflict that arose from a philosophy of “might is right” associated with unbridled greed and power. It ended with the defeat of Germany. Britain enlarged its empire and Germany prepared for the Second World War on a wider and more destructive scale. Japan emulated the West, conquered Korea and invaded China but appeared to be in a stalemate in China. Japan prepared to enter the Second World War with a powerful army, navy and air force.

The western powers gave little credence to the suggestion that Japan’s ambition was to conquer the Asian colonies of Britain, France, The Netherlands and the U.S.A. We in Singapore were convinced that Britain and the U.S.A. were invincible. Many of my white colleagues laughed off the possibility of Japan entering the war. They pointed out that the Japanese military machine was bogged down in China. “Their war planes are like the Japanese paper houses, and will be blown out of the sky by the breath of our buffalo fighters! The British defence preparations in Singapore, with pill boxes along the southern coast will pulverise the Japanese navy”. Holgate (who was Principal of Raffles Institution at that time) differed from this view. He took the Japanese danger seriously, and thought the British defences in Singapore were inadequate. He feared that the Japanese had not shown their real might in China. However, he was in the minority. We Singapore citizens believed what the British news media told us which was in line with the ideas of our white colleagues.

Mangalam and I joyously looked forward January 1942 when Mahendran would begin school in Telok Kurau School and we enjoyed Indra’s progress in reading. Both our children were avid for learning. In December 1941, we joined the Kandiah family for a holiday in Port Dickson. Kandiah feared that Japan would enter the war against the allies. He wanted to make arrangements in case anything happened to his youngest daughter, Saras, who had no children. Her dowry would revert to him, and if he should die, it would come to Mangalam as Trustee. He drafted a will for Saras to copy and sign and told Mangalam to check it. Mangalam just accepted the signed will without even reading it.

On the 8th of December 1941, radioed news of the bombing of Singapore shocked us. I rushed back to Singapore immediately, fearing looters would ransack our house for furniture and clothes. I was just in time to stop the looters taking our furniture in Haig Road. I then returned to Port Dickson to bring my family back to Singapore.

News from the western media buoyed us up. The American fleet was concentrated in Pearl Harbour guarding the Pacific. The British warships Prince of Wales and the Repulse were steaming to the South China Sea to supplement the American naval power. Everyone expected that Japan would veer away from Malaysia and Singapore. The next radio news shocked us tremendously. The Japanese air force had smashed the American naval forces at Pearl Harbour and sunk the so-called invincible British ships on the 10th of December 1941. In shock and sorrow, many whites fell to the ground weeping. We soon realised that the western powers had been ignorant of Japanese naval and aerial power. It became obvious that the Japanese forces would sweep through the Philippines, Malaya, Singapore, the East Indies and Burma. Would they take Australia, India and Ceylon? Did they have a large enough army, navy and air force to conquer and hold all of them?

Schools reopened in January 1942, and during the very first week, Japanese bombers swooped low over St Andrew’s Cathedral and Raffles Institution. On hearing the air-raid siren, the staff and students rushed down to the field. We threw ourselves flat on the ground. My white colleague, Cobb and I lay on the ground beside the canal. He covered me with his raincoat and lay down close to me keeping me against the canal wall. When I protested he remarked, “I am old, you are young, and you should have better protection!” (Cobb had been my Latin teacher in 1924, and now was retired and reemployed in R.I. A few days later he was on a ship being evacuated, the ship was bombed and he was one of several killed at sea). I saw bombers release bombs as they flew over the cathedral. I feared that the bombs would hit our school, but they fell on the Kallang airport and surrounding areas.

After the bombing of the Kallang Air Port, the authorities closed schools and geared Singapore’s resources for defence and protection of the people. Britain had recruited Indian regiments to bolster the defence of Singapore, but the ships that were to transport them, the Prince of Wales and the Repulse were sunk in the South China Sea. A tiny local volunteer force augmented the existing British, Australian and Indian regiments. The authorities put the First Aid and Air Raid Warden units on alert. Teachers were called up to serve either in the Ambulance Corps or as Air Aid Wardens. I was an Air Raid Warden and initially stationed at the Municipality. We were shocked to see a wave of Japanese bombers, unopposed by any British fighter planes, coming in broad daylight, flying low over us to drop bombs on Kallang airport, the Beach road market and Rochor road area killing hundreds of civilian men, women and children. I was in the second team of wardens and helped to pick up nearly 90 bodies in the market alone! It was my first experience of such carnage and it took me a long time to recover from the shock.

We lost confidence in the ability of the string of ‘pill-boxes’ along the southern coast of Singapore to keep the Japanese invasion at bay. We dreaded carpet-bombing by the Japanese. If the Japanese concentrated their bombing on the pillboxes and the concentration of British defences, it would trap the civilian population in the fighting, bombing, shelling and shooting. Many Singaporeans joined British civilians for evacuation by ship to take refuge in India and Ceylon. Some of them died when the Japanese bombed their ships. We set about to devise whatever protection we could, such as building our own air raid shelters and stocking up on rice and tinned provisions.

Contrary to our expectations, instead of launching a naval attack from the south of Singapore, the Japanese landed their invasion forces in Kota Bahru on the northeast coast of Malaya. They pulverised the British army with bombs and shells, fanned out west and advanced at lightning speed down Malaya. The only meaningful pitched battle was at the Slim River and it ended within a few days.

At the same time, the bombing of Singapore continued with swift strikes and little resistance. The British fighter planes appeared to take to the air only after the Japanese bombers departed. Why did the Japanese bomb the civilian population? The only explanation I could think of was they wanted to scare the people and prevent them from taking up arms with the British, or they wanted to punish the Chinese population of Singapore for the financial aid they had given to China.

The British army commandeered all housing in Haig Road quarters. We had to move out, and my friend T.E.K. Retnam took us in as guests in May Road. From there we witnessed the air battle with British artillery firing their guns and Japanese bombing and shelling the island. We were lucky to escape when a shell hit the house next door. It only caused roof tiles to clatter into the upper storey while all of us were asleep on the ground floor under a sturdy teak dining table with mattresses piled on it. I spent my days taking shelter from bombs and shells, picking up the dead, writing death certificates and buying canned foods. One nightmarish experience was taking refuge under the concrete slabs in the mortuary of Tan Tock Seng Hospital when the Japanese shells fired into that area.

Singapore had never experienced war or enemy occupation. Apart from the bombing and shelling, we feared our water supply from Johore[1] would be cut off. The Chinese community feared reprisals for the financial aid they had given China. Many of us, employees of the British government, feared we would have no means of earning to support ourselves. Numerous families made and hoisted Japanese flags hoping that by welcoming the invaders they would avoid ill treatment.

T.Mori, a Japanese who settled in Malaya, had been my schoolmate at the M.B.S. and later at Raffles College. We were close friends. He and his family lived in Malaya. When war broke out, the British took him and his family as prisoners of war and transported them through Singapore to India. While imprisoned in Singapore’s Changi Prison, he wrote me a letter for help. However, his letter reached me only after he was transhipped to India and my reply never reached its destination. After the war, I had difficulty getting him to accept that I received his letter too late even to contact him in Singapore.

The British surrendered and we had relief from bombing, shelling, and fear about our water supply. Chaos reigned for a few days. A few people looted bags of rice and other commodities from military stores. Several women and girls suffered rape. The Japanese herded almost all young adult male Chinese into concentration camps. Some of them were released but several thousands were either carted as labourers, or were summarily shot and buried. Those who went to the camps seldom returned. My friends, Koh Eng Kwang of St Andrews School and Chua Yew Cheng of R.I. were among them.

[1] The island of Singapore does not have sufficient water sources for its population. It received water supply from Johor, which is the southernmost state on mainland Malaya.

Start of the Japanese Occupation

After the British surrender, I tried to return to our Haig Road house. There were Japanese sentries at all road junctions, and I had to give them my Omega watch. A few days later, we moved back to Haig Road. An incident that stands out in my memory concerns Eric, T.E.K’s five-year-old son. He was fond of us, and obtained his parents’ permission to accompany us for a few days when we moved back to Haig Road. At the end of his stay, his cousin picked him up on a motor bike to return home. Soon after they departed, we heard a long series of bomb blasts coming from the city area. We were terrified for Eric. Next day we learnt that the blasts were in the Geylang English School building. The Japanese had stored bombs and shells in the building and the blasts were set off by British prisoners of war who were taken there as labourers. The blast razed several buildings to the ground and many Japanese soldiers and Singaporeans lost their lives. Eric and his cousin escaped by taking shelter in a deep drain. We were most grateful that Eric’s parents did not blame us for putting Eric in danger and continued to be our friends.

The Japanese army soon commandeered our Haig Road house and we had to move out. We rented a little bungalow off Moulmein Road, and managed to hire a lorry to move the remains of our furniture that survived the looting. The Japanese also commandeered our house in Goodman Road and our car. In order to buy food, I waded across storm drains and through marshes to reach Chinese villages to buy vegetables, chicken and pork. We lived in fear of Japanese soldiers raiding homes to rape girls and women.

Father-in-law, his daughter and son die

While we adjusted to our new life, we received the shocking news that the Japanese bombing of Kuala Lumpur in January 1942 had fatally injured my father-in-law in his office. On hearing the air raid siren, he had waited for all staff to go to the ground floor, and when he finally did descend, instead of lying down on the floor as the others did, he stood at the entrance to the corridor. A shrapnel from a bomb dropped on the mosque across the Klang River severed his intestine. He died on the operating table.

Soon after, we received more news that was shocking. My brother-in-law, Thambyiajah was seriously ill with typhoid. He sent a message requesting me to go to Kuala Lumpur urgently to take possession of documents for Mangalam that his father had left with him. I undertook a train journey that took nearly two days. When I finally arrived at the house, I was shocked to see signs that there had been a funeral. I assumed that Thambirajah had passed away. But no! It was my youngest sister-in-law, Saras, and her unborn baby, who died from lack of medical help during a difficult labour. I visited Thambirajah in hospital, and he appeared to be recovering. I collected the documents and returned home after another tiring long journey, only to learn that Thambirajah too had passed away.

Mangalam was unwell when I returned with all this tragic news. She had lost her voice. I feared that the shock of the deaths of three loved ones would cause her to faint. Fortunately, she was not the fainting type. She worried deeply when any one dear to her fell ill. She did all she could to nurse the patient. However, she accepted bereavement stoically, although she grieved deeply.

Mangalam looked at the documents Thambirajah sent, and was shocked to find that in her will, Saras had omitted the section that required her property to revert to Mangalam as Trustee. Father-in-law had died before Saras. There was no question of the property reverting to his estate; her husband, Arunasalam, was the beneficiary to her estate. Both he and I were executors of the estate, but he refused to be an executor. Mangalam refused to accept the legal position. She argued that according to the law in Ceylon a property given as dowry should revert to the father’s family since Saras had died without leaving any child to inherit it. Lawyers pointed out that the Ceylon law does not apply in Malaya. Mangalam wanted to consult lawyers in Ceylon. As executor of the estate, I was in a difficult position. Arunasalam, however, waited patiently for me to resolve the matter. Many years later, the decision was that the estate would had to go to him. The entire episode soured my relationship with Arunasalam who had been a good friend in earlier days.

Working as a teacher under the Japanese regime

Schools reopened. Teachers did not know even a word of Nipongo (Japanese) but we had orders to teach in that media. We bought whatever books we could, learnt some words and sentences and attended Nipongo classes under Japanese soldiers. When we sat for exams in the language the supervisor remained stock still in his chair and all of us, including those who knew very little, scored over 90 marks.

I walked to most places because there was hardly any transport. I used the walking time to master Japanese vocabulary. Every morning, at school, we had orders, to turn eastward to pay our respects to Teno Heika, the Japanese god on earth. Many of us mumbled curses at him. In class, many of us put Japanese sentences on the board, and displayed drawings with words and phrases on the walls to exhibit our loyalty in teaching Japanese. However, we used English in our real teaching. We set up sentries who would tell us if a Japanese person was visiting the school. We would then revert to the words and phrases on the board and the walls. Teachers and schools had varying experiences. The teachers who learnt the Japanese language quickly and became proficient gained acceptance as being loyal and received favours. I lost touch with my fellow teachers in in March 1944, and do not know how they fared during the last 15 months of the Japanese Occupation. After the liberation, I learnt that several had died.

Life during the Japanese Occupation

The bombing and the Allied defence caused much destruction. During the four years of Occupation, the scarcity of essential food items increased rapidly by the day. Those who had the means bought on the black market while those who were in good books of Japanese officials could get supplies. Wherever possible, people resorted to rearing poultry, pigs and cows and cultivating tapioca and vegetables. Too many, however, suffered from malnutrition and died.

My days were long and tiring. I walked to Victoria School to teach Japanese, ate my packed lunch, and walked to St Joseph’s Institution to learn the language. To supplement my very inadequate salary, we reared poultry to ensure our own supply of eggs and meat. Mahendran had fun feeding the chickens and ducks, picking up eggs and watching cockfights. I had time with my children only when I returned home late in the evening, joined Mahendran and Indra to feed the chickens and later, had dinner with the family.

A little incident provided excitement. We had a poultry yard within view of our bedroom window. Light from our bedroom partly lighted the poultry yard. One night the poultry ran about making excited noises. I shone my torch, and saw a cobra getting back into a hole in the edge of our garden. Using a long bamboo pole and standing within the safety of our room, we poked into the hole from our window, but the cobra had gone deep inside. We figured that cobras habited the old graves opposite our residence. We discouraged further cobra visits by lighting up the yard.

Life was very hard. Our attitudes changed dramatically. Singaporeans were largely Asian economic migrants who sought a better life than in their countries of origin. We had gravitated to Singapore believing the White man’s rule would give us a better future, and we grew up believing the White man was superior. Now, such superiority just vanished. To my mind, this was the end of the British Empire. Now we became subjects of Japan without the means to earn enough to support our lives. No one believed there would be any ‘Co-Prosperity’ if Japan won the war like the Japanese propaganda machine wanted us to believe. The new imperial master very likely would be a slave master. We prayed the Allies would win the war and retake Singapore. Subsequently we could gain independence. Chinese-educated Singaporeans even dreamt of converting Singapore into a Chinese colony. For some time we listened clandestinely to British and American news broadcasts of the war in Europe and in the east, telling ourselves victory was just three or four months away. However, several listeners were arrested, and we gave up and discarded our radio.

More tragic deaths – and no time to mourn

During the War years, I suffered the loss of several close friends, and hardly had the time to mourn them adequately because of the demands of daily survival. One such loss occurred while I made my painful journey to Kuala Lumpur to learn of the death of three family members. My close friend and colleague, Paramsothy collapsed with bleeding in the brain. I visited him in hospital as soon as I returned. He was in a coma and passed away shortly afterwards. A few days later, my dearest friend, Dr. Chan Jim Swee became seriously ill with double pneumonia. The hospital to which he was admitted was under military security control, but I managed to sneak in and see him. He was delirious, and struggling against bands holding all his limbs to the bed. It was terribly distressing. I was helpless because my visit was illegal and there was no doctor whom I knew in the hospital. It was a depressing relief when he breathed his last.

Another good friend, A.C. Rajah had been denied a job. He lived near us at that time and spent much time with my family, thus giving them companionship until the latter part of 1943. A few months before I took steps to migrate to Kuala Lumpur, A.C. went against his father’s objection and married a Christian girl, Mercy. He was posted to the Japanese Sime Road Training centre. His life became too busy and we lost the close contact we used to have with him. On the morning of our clandestine flight out of Singapore (see later paragraphs) we heard the most distressing news that he had committed suicide at the Japanese Sime Road Training centre. I rushed to pay my last respects to him before I left with my family for the railway station. We never heard any convincing reason for his desperate and shocking action. His death was a great loss not only to his family and loving friends (including my family) but also to education in Singapore. He was one of the most brilliant teachers.

I guess I was fortunate to escape injury, starvation, ill health, and escape the pressure to join a resistance movement.

Rajendran’s arrival

We were living in Moulmein Road. At midnight, on the 23rd of August 1942, Mangalam went into labour. I had lost my car, and taxis were unavailable. I rushed to a friend Dr. Doraisingam in Norfolk Road. He had made a standing offer of transport in any emergency. He came readily and took Mangalam to Dr.Menon’s Lily Clinic in Serangoon Road and Rajen was born. Mangalam had frightening nightmares but was otherwise in good health.

As a baby, Rajen had no problems. He loved it when I carried him out for walks and would chew my shirt collar. For Indra, he was like a real-life doll; she made up little dramas with him and he learnt to run after chickens, ducklings and turkey chicks. I think that Rajen’s arrival at that time had a significantly positiveeffect on Indra’s development. She was at an age when in normal circumstances she would have enjoyed playing with dolls but she had only the dolls bought before the war. Instead, now she had a real-life doll who must have aroused motherly instincts in her very early on in life. In addition, the doll did not remain the same; it kept transforming week by week and there was no need for us to buy a succession of dolls. Later she had another real-life doll – Leela!

I suspect Mahendran, on the other hand, had mixed feelings. He loved having a brother but he was a demanding type, wanted parental affection and could have felt some jealousy. I had little time at home. His mother had Rajen and later, Leela to care for. Mahendran had less play time with Indra, and he had no other boys as playmates as we did not send him to school.

Fortunately, we still had our male servant Somoo, on the understanding that we would pay him full wages after the liberation. He was versatile as a cook, general handy man, baby sitter, toy maker and playmate for Mahendran. Thus, Mangalam did not have to worry about cooking or caring for Mahendran and Indra, as they were old enough to look after themselves, and even help with the babies.

Financial issues

Meanwhile, other financial issues complicated our life. The Oriental Bank made repeated demands for settlement of an overdraft of $4000. Mangalam argued that this demand was on Saras’ property. I am not sure. We had no money to pay the bank. If the overdraft indeed was on Saras’s property, the logical step would have been for me to sell the property, settle the overdraft and give the balance to Arunasalam, the legal beneficiary. Mangalam was against this step, and instead, decided to sell one of the vacant lots of land in Kuala Lumpur that she had inherited. I asked my cousin Thuraiappah, who had recently sold one of his two houses, to find a buyer. Instead, of selling, he offered us a loan of $4,000 on the understanding that we would reimburse him after the Occupation. I believe I am right in conjecturing that the overdraft we settled was on the properties of my father-in-law. When the issue of Saras’s property was settled later in favour of Arunasalem, Mangalam did not ask that the overdraft amount be repaid to her. Disputes such as this one, contributed to differences between Mangalam and me.

Leela’s arrival

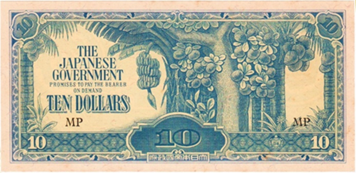

On the 4th of February 1944 Leela was born, inflation was at its height. My monthly salary in the ‘banana currency’[1] could only buy us food for three or four days. We had no savings. We kept ourselves alive by selling Mangalam’s jewelry to supplement my earning, and this would soon run out. Even buying milk for Leela would be a big problem. We decided to move to Kuala Lumpur and live in Saras’s dowry house in Kuala Lumpur. I was its sole Trustee. I could not look after the property from Singapore nor find any tenant. By occupying the house, I could kill two birds with one stone. I could look after the property while growing vegetables, rearing cows for milk, and poultry for eggs and meat for the family.

[1] During the Occupation, the Japanese government printed and issued its own currency. Use of the previous Straits $ was forbidden. However, the black market was a very active and the entire population participated. The Japanese currency, known as “banana currency”, rapidly became worthless due to inflation. Salaries were paid in the ‘banana currency’ Black market transactions dealt in Straits currency, which we expected to use after the Allies retook Singapore.

Migrating to Kuala Lumpur

Resigning my teaching appointment and migrating to K.L. proved unexpectedly difficult. I sounded out E.V. Davies, the administrator of schools, about my intention to resign. Without any ado, he warned me that I ran the risk of being sent to Thailand as a labourer. Several unemployed teachers were available, yet he spoke as though I was indispensable. I waited for some weeks and sent in my letter of resignation. He rejected it. I believe he had his dagger in me for refusing to become a member of the Syonan Teachers’ Association, for not joining the Indian National Army under Subas Chandra Bose, and for being a friend of A.C. Rajah who had married a Christian in defiance of parental objection. I was obliged to resort to secret moves. I discretely sold my furniture and Mangalam’s jewels, and changed the ‘banana currency’ into Straits money and planned to leave Singapore secretly with my wife and four children.

Mangalam would not rely on hiding the money in our bags of clothes but tied it in a sash around her waist. At the railway station, passengers queued up for a thorough body search. We knew that if the authorities discovered Straits currency they would confiscate it and throw all of us into jail. I was terrified. Mangalam appeared calm but I was certain that she was equally scared. We could not slip out of the queue. I foresaw torture in prison, worse for my wife. I was drenched in sweat. Just before Mangalam’s turn in the queue, Leela, our one-month-old baby, in her mother’s arms, started to cry loudly. The baby’s cry seemed to appeal to the humane instincts in the sentry, and he let Mangalam through without a body search! A baby to the rescue; and who said that all Japanese soldiers were heartless? We had come through our worst war experience.

Life in Kuala Lumpur

After a tedious and exhausting journey, crushed between an overload of passengers, we arrived in Kuala Lumpur. We spent the first two weeks as guests with Mangalam’s elder sister. I heard that the Japanese Military authorities had asked the Police in Kuala Lumpur to trace my whereabouts and send me back. It did not happen and I dismissed it as a rumour. I bought an old bike and learnt to ride it. We moved into Saras’s dowry house, which was a four roomed, wooden bungalow in a spacious compound in Keng Hooi Road. We arrived with a few of the chickens, ducks and turkeys we brought from Singapore that survived the journey. I bought a few more, and two cows and a goat. Life became healthier. I rode my bicycle to buy food, and could balance on it, even with a bag of rice (bought on the black market), or a heavy tub of liquid soap or a bag of fertilizer.

One day, I rode the bike from about 7 am until midnight to buy a cow and calf from a neighbouring town, and brought them home. I did the laundry by hand, fed and milked the cows, dug the ground and planted vegetables. Somoo helped in digging the ground, clearing cow dung, distributing milk to a few neighbours and collecting payment from them. Learning to milk the cows was difficult. My fingers tired too soon. Once a cow kicked me and I went sprawling under a shower of milk! Mahendran fed the poultry, collected turkey eggs from bushes in the adjoining compound and stopped fights between the cockerels and the Manila drakes (of course after witnessing the fun for some time). With help from Indra, Mangalam looked after Rajen and Leela. She ironed the clothes and taught Mahendran and Indra. On the black market, we bought rice, sugar, salt, spices, cooking oil, soap and feed for the cows and poultry at exorbitant prices and paid for medical treatment. Money ran out. Mangalam sold another vacant lot of residential land to help us as well as two of her sisters. We converted the balance into Straits currency to use for future needs.

We permitted a small village of communists who lived behind our house in Keng Hooi Road to tap water from our supply. They became our friends. They boosted our sense of security by proposing to take us into the hills if the allied forces landed to fight the Japanese.

Our social life

Our social life was very restricted, but we did manage to socialise with a few well-established families in Kuala Lumpur. I often met my boyhood friend Chanan Singh, at a shop in the town. He had exchanged his car for a small lorry, transported produce from his garden in Kajang for sale in Kuala Lumpur, and earned good money. He gave me tips on where I could buy black market commodities. Another friend was Lee Kuan Yew, an ex-teacher at Victoria School (not the LKY who later became Prime Minister of Singapore). He was Commissioner of Estate Duties under the Japanese. He gave me information on the cheapest source of Thai rice on black market. In addition, he updated me on news about Allied successes in the war and American advances in the Pacific area. Such news buoyed up our spirits. My cousin Thuraiappah was a welcome frequent visitor at home. He was the dispenser/pharmacist at a private clinic and charged discounted rates for our medical supplies. These were the cheerful moments of life in Kuala Lumpur.

Trials and tribulation during the final months of the Occupation

During the final months of the Occupation, we were unlucky to lose both our cows. A cobra stung one of our cows and she dropped dead suddenly while drinking water. The other cow sustained a cut on one of its teats, and would not allow any milking. She went dry. Mangalam sold a second plot of residential land to buy a new cow. This cow cost a pretty packet but gave little milk! From the proceeds of that sale, Mangalam also paid off the $4000 debt to Thuraiappah.

Just as liberation was around the corner, Rajen came down with double pneumonia, and caused us immense worry. However, we were able to get medical treatment for him.

The Allied forces began their carpet-bombing of the Sentul Railway workshops that were a mere half mile away from our house. We witnessed the low flying American bombers as they released bombs directly over our heads. We knew that they had aimed at the target half a mile away. Our communist guerrilla neighbours had alerted us and said the residents in the Sentul area were warned to clear out of the place. However, some civilians died in the bombing, a few in their air raid shelters, while others had not heard the warning.

The Keng Hui Road phase of our life was very tough and costly but much better than life would have been in Singapore. We had good food and led a healthy life. I escaped the stress of working under the Japanese, and we were fortunately able to spent time together as a family. We coped well, under the circumstances, with the adversities of enemy occupation. The children had close parental care, with their mother teaching them and we had good medical care. We also had Somu, whose help greatly eased the daily chores of living. He was loyal and had been with us from his early teenage days.