Marriage?

While most of my colleagues prepared for marriage, I saw no prospect of it for myself for various reasons. I would not consider it unless I came across a girl I truly liked. My community did not allow girls to meet boys and stopped their schooling in their early teens; therefore, I had no opportunity to meet prospective brides. Families arranged marriages using intermediaries who approached eligible bridegrooms. The most desired bridegrooms were doctors, lawyers, engineers, teachers, and last of all clerks. Caste and family background were vital. I was not interested in an arranged marriage!

The Kandiah family: a twist of fate

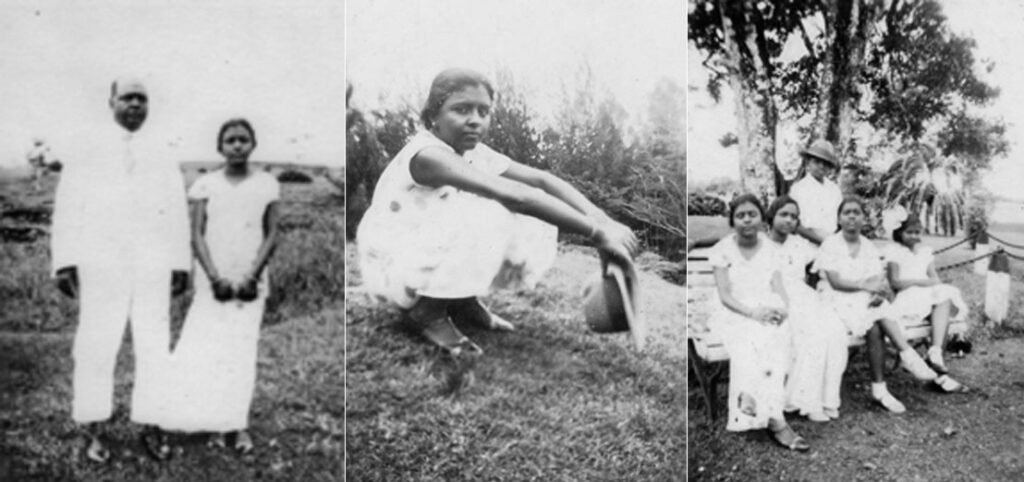

My friendship with Thambirajah (eventually my brother-in-law) matured at Raffles College. During a visit in 1931, I met his father, the redoubtable Mr. Kandiah, and found good rapport. Thambirajah had told him much about me, including my boyhood days and the warm reception Mrs. Kandiah had given me. Unusual for those days, Kandiah felt free to talk to me about his children, and told me how he ignored frowns of relatives and friends in deciding to allow Mangalam, his second daughter, to become the first Hindu girl in our little community to undergo teacher training. I voiced my opinion that the Chinese in this country would outstrip our community unless we forsook our Jaffna village traditions. He was pleased and introduced his daughters to me. They had grown so much since 1919 that I could not recognise any one of them. The two eldest had been tomboyish, but now they were lady-like; the second, Mangalam, looked the most intelligent, and was very confident in responding to my enquiries about her teacher training. Her sparkling eyes betrayed that she was assessing me critically, and gave the impression that she didn’t like the way her father had called her sisters and herself to introduce us. Kandiah invited me to join his family at dinner and showed the same cordiality his wife (now deceased) showed me 12 years earlier.

An Unexpected Visitor

One evening in April 1932, I was surprised to receive a visit from Mr. Kandiah. I wondered why he came. Was it to seek my help to get Thambirajah who had been retrenched due to the Great Depression, or was he coming as traditional intermediary to propose an arranged marriage for a friend’s daughter? My mind raced for a quick and polite way to refuse. He soon launched into his subject:

“Have you accepted any marriage proposal?”

“No, I have not”.

“Would I consider any?”

“Not likely”.

“Why? Are you disappointed in love? Or still in love with the girl who had rejected you?”

“No.”

He went on to frankly ask confidentially if I would agree to marry his second daughter. He trusted me to keep it a secret. He had a high opinion of me, had made enquiries and my background impressed him. This was an utter bolt from the blue! In our community, intermediaries brought proposals for marriage, so that there would be no loss of face if the proposal did not succeed. A father did not make a direct approach to a prospective groom unless it was a close relative. Mr. Kandiah was a very prominent man in our community. Yet, he personally had come to me and not sent an intermediary. I was dumbfounded. I realized it was impolite to remain silent for long. Therefore, I thanked him for his generous opinion and graciousness in ignoring tradition to speak to me personally. However, I was entirely unprepared. I was not been thinking of marriage for reasons of which he was unaware. I was an abandoned son of a man who married again after abandoning my mother and subsequently raising another family. I also told him I had been disappointed in love. If the girl I married threw any of those facts in my face during a domestic quarrel, I was not sure how I would react. My father abandoned me, and I did not want to repeat that performance and walk out of a marriage in anger and cause suffering to my children such as I had suffered. Mr. Kandiah waited until I finished, then assured me that he had not only made enquiries about me but had also made his own assessment of both my character and feelings. He was sure his daughter would promise not to hurt my feelings if she married me.

I had met and spoken with Mangalam. I was sure I would never meet another girl her equal. On that note, I said that I would be glad to accept his proposal. I stipulated that Mangalam be told about my fears. She should think about them and be certain she could indeed brush aside as unimportant my romantic episode and my father’s past behaviour. It was the custom in our community that a bridegroom would demand substantial dowry, in the form of cash, property and jewelry. I specified that I would not accept any dowry. I wanted Mangalam to make the decision on whether we would get married, after we met and got to know each other, and she was certain I was the person she wanted in her life.

Mr. Kandiah told me about his investments and the mortgages he had raised to buy his properties. He intended to give dowries to his daughters. He asked if I would stand in the way of his giving Mangalam her share of the inheritance. I told him that issue was between father and daughter and I did not wish to be involved. He departed saying that we would clear all issues by correspondence.

Wedding

Our courtship consisted of a rapid exchange of letters and several visits that I made to Kuala Lumpur. The Kandiah family accepted my invitation to spend a week with me in Singapore at the end of 1932. Our wedding took place in in Kuala Lumpur on 15 April 1933 past midnight, in Circular Road at the house where, in 1919, I had seen the five-year-old Mangalam romping about and envied her and her siblings for the family life they were having and I did not have.

Adjusting to Marriage in the 1930s

My life did not give me the ideal dream of living happily ever after. As the saying goes, it takes two hands to clap. However, if the nervous system is faulty, the moving hands may miss each other at times. The relationship between my wife and myself has been somewhat like that. However, we managed as well as most couples.

I was married two short years after graduating and commencing work. With a salary of $230 per month, it was a short period. However, I managed to settle my financial obligations, set myself up with a good wardrobe, establish a home and enjoy a holiday. I was frugal and saved enough for a simple wedding but could not afford a car. In keeping with my decision not to accept a dowry I rejected my father-in-law’s offer of his used car and Mangalam was obliged to forego that luxury. My salary was adequate for a couple of our standing to live a comfortable life.

Mangalam was eager to work, but the slump prevented work for newly married female teachers. Her father had given her a piano; we had a gramophone with many records and a library of books for her to amuse and edify herself. In addition, she thought of preparing for an overseas external University degree and she became the voluntary secretary of a ladies’ club and thus did not feel lonely. To free her from daily household chores, I retained the services of a full-time cook and general servant.

Our lifestyle in the 1930s

After our marriage we moved from Rangoon Road to Dunman Road and then to Moulmein Road where Mahendran and Indra were born. While living in Moulmein Road, we employed Somoo, a teenager who turned out, under Mangalam’s training to be a good cook, a general servant and a baby sitter. He stayed with us through the War, the Occupation and immediate Post War years and when he left us, he had saved a tidy sum of money from his wages.

| Hourse rent | $30 |

| Cook’s wages | $15 |

| Transport | |

| Club & Assoc fee | $4 |

| Kurau fish, Mutton | .40 cts per kati. (we bought half kati each week) |

The cook went to the market on weekdays while I went on weekends and holidays. The cook would usually buy chicken, pomfret, mackerel, prawns and other types of fish and vegetables while I bought our provisions for cash at Govindasamy’s shop.

My brother Kumarasingam died suddenly in 1934 and I started sending $10/ a month to my widowed sister-in-law. Early in 1935, their eldest son, Kathirarvelu, who had never settled down to studies, arrived in Singapore and Dr.Subramanyam asked me to care for him. I enrolled him in the Y.M.C.A. classes to study shorthand, bookkeeping and typewriting.

I was determined never to incur any debt. I traveled to school by bus until 1935 when I bought an old Singer car for $250, with a down payment of $50 and paid instalments over the next 10 months. I restricted my games, for some time, to cricket and hockey. We rarely went to a cinema because Mangalam was not keen. I had saved some money and bought a vacant plot for $500/ and later sold it to purchase the Goodman Road vacant lot to build a bungalow with the help of a mortgage.

I was so committed to teaching, extracurricular duties, editing Chorus (the journal of all teachers’ associations from Singapore to Penang), and playing cricket, hockey and the occasional tennis that I did not give Mangalam as much companionship as I should have done. However, she busied herself with honorary secretarial work for the fledgling Ladies Union, going around collecting donations and studying to sit for the London University external examinations.

Our first two babies arrived

Mahendran was born on 7 March 1935 and Mangalam’s interests and joy centered on him. Mangalam discontinued her studies and hoped to resume them later on, but that did not materialise when she started work as a temporary teacher doing afternoon classes in September 1935. We employed a full-time amah for the baby but Mangalam was too much of a perfectionist to relax. She looked after baby Mahendran in the morning, persuaded me to reduce my extracurricular activities in the afternoon to keep an eye on how the amah cared for him in her absence. Mahendran was quite a handful. He was colicky, had frequent constipation, slept by day but kept his mother awake after 10 p.m. I was too sleepy to give her much assistance. Mahendran’s redeeming feature was his early display of sharp intelligence and charming ways. Mangalam’s pay of $100/ p.m. went to her father to help him service his mortgages. We had to husband our resources and could not save anything for a while.

Mangalam probably was exhausted caring for her demanding infant and this made her very irritable with me. It drove her into rages especially when she was expecting our second baby. Our second baby, Indra was born in October 1936, and Mangalam had to stop work for about a year. Fortunately, Indra was a relatively trouble-free baby in her feeding and sleep habits. Mangalam went back to work and I cut down on my games.