Success in our fight for Back Pay: 1947

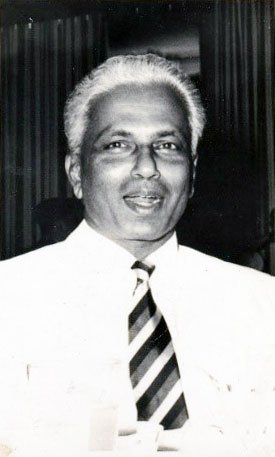

I was the chairperson of the Singapore Teachers’ Association. In that capacity, I became a member of an Action Committee representing all employees of the Government. The Committee chose me as one of the three delegates to appear before the Governor of Singapore and members of the Executive Council to present the case of all civil servants for Back Pay for the Japanese Occupation period. I had to assume the role of lead spokesperson, because our leader was not good at arguing the case although he was good at presenting statistics, while the second delegate became tongue tied in the presence of the august officials.

When I started answering the questions from the officials, the Governor asked me irrelevantly, “Mr. Ambiavagar, I believe you are a Jaffna Tamil?”

I responded, “Yes, Sir, but I don’t see what that has to do with our appeal for Back Pay?”

The laughter from the Executive Councillors gave me the courage to answer all subsequent questions fired at me.

We were successful in getting the back pay!

I felt grateful for the school days’ debating experience at R.I. that had laid the foundation for that success.

Dirty politics in the Teachers’ Union. 1948

While readjusting with my family and myself to life in Singapore, my mind aspired to meet new challenges. Singapore, like all other colonial territories, feverishly wanted independence. Communist elements infiltrated trade unions and Chinese High schools. The Malayan Democratic Union (MDU), that had English-educated leaders, some of whom had Communist ideologies, gained prominence. Other political parties like the Progressive Party sprang to life.

I had a firm belief that civil servants should not participate in politics, nor be members of political parties. Furthermore, I preferred to be free of party rules. I had good friends who were politically inclined including A.P. Rajah, and David Marshall[1] whose wrath I incurred by telling him that he should join forces with C. C. Tan. [Editor’s note: Marshall was leader of the Labour Party while C.C. Tan led the Progressive Party. Marshal eventually defeated Tan in the 1955 elections, and Marshall became Chief Minister of Singapore]

All categories of civil servants formed unions to demand various rights from the colonial power. As chairman of the Singapore Teachers’ Association, I led the fight for revision of salaries, creation of promotion posts and equality for men and women teachers. The 1947 revision of salary scales was inadequate. The authorities told us to form a trade union like other government employees to conduct further negotiations. The average teacher thought that trade unionism was for labourers who could go on strikes. If management locked out labourers, they could hop from one kind of work to another. Teachers, on the other hand, had nowhere to go if management locked them out. Therefore, most teachers refused to support the proposal to convert our association into a union. It took a great deal of effort and careful persuasion to convince teachers that we had to comply with the conditions in order to push our claims. If rebuffed, we need not go on strike unless at least two thirds of the members voted to do so. Eventually, we obtained their support. The Association Committee drew up a trade union constitution ad obtained approval. Meanwhile, a vacancy arose in our committee, and P.V.Sharma filled it, just at the time that we were preparing for our inaugural meeting. I knew he was a member of the Malayan Democratic Union (M.D.U.) which, although led by communists, had prominent non- communist leaders. I thought Sharma was like Dr.B.R. Sreenivasan and Yong Nyuk Lin who were merely anti imperialists, not communists. We prepared for an inaugural meeting, and proposed to hold it in St Joseph’s Institution (SJI) hall where we had held all our meetings when were an Association. However, we learnt the Brother Director of SJI did not like the idea. Sharma suggested hiring the M.D.U. hall and we did so.

Two or three days before the inaugural meeting, Sharma called on me to discuss potential office bearers, and a strategy for the revision of salary scales. He argued that without political support we would fail in our mission. I reiterated my view that civil servants, as government employees should remain neutral in politics. Sharma insisted that unless we came under the MDU wing, we would get nowhere. I realised he was a communist and I told him bluntly that I would have nothing to do with politics. Immediately, Sharma walked out and I watched as he went to my colleague Balhetchet’s gate, which was a short distance away. I guessed that he was going to persuade Balhetchet to stand for election as President. On the morning of the meeting, I learnt that Sharma and his friends had gone to several schools telling teachers that Neilson (Director of Education) had bought me over with an offer of a scholarship to U.K. to study for Honours in English[2] if I sabotaged the Teachers’ Union fight for a revision of our salaries. Sure enough, when the meeting commenced, every time I stood up to speak, a small group in the audience booed me a traitor and told me to sit down. I walked out of the meeting and Sharma took charge of the new union! The newly formed Singapore Teachers’ Union went on to fight for parity between all categories of teachers regardless of their educational background. I doubted this would find favour with the authorities.

[1] Marshall (who later became the Chief Minister of Singapore) was too much of a gentleman to be vindictive. He was a great leader but his weakness was his inability to control his animosity towards other leaders and resultant dependence on too small a core of friends who were themselves not united. Moreover, he was Jewish while the predominantly Chinese electorate were largely Chinese-educated and the leaders had a strong core of Communists. Marshall was non-Chinese speaking and anti-Communists. (Ambiavagar’s note)

[2] The fact was, a few months earlier, I applied for a coveted civil service position in the Department of Labour, with backing from Shaw and Holgate (Principals of R.I.) However, Nielson, the Director of Education called me to his office a few days before the Inaugural meeting, and persuaded me that while he would not actively oppose my application, he felt I should remain in the education service since I would eventually rise in it. I had no option but to accept the status quo.

The Malayanisation Commission

The David Marshall government appointed the Malayanisation Commission under Dr.B.R. Sreenivasan to study and report on whether all expatriates in the civil service could be displaced by Asians. Representations were invited. As President of the Graduate Teachers’ Association and at the request of the Singapore Teachers’ Union, I appeared before the Commission to give the views of both organisations.

Reports of the proceedings indicated that Malayanisation would begin soon. All expatriates in government service realised that Singapore was moving fast towards independence and that their days here were numbered. Senior expatriate officials like Howitt, Purcell and Ince readily accepted Malayanisation and helped to implement it. Only some junior expatriates who had expected to reap the fruits of colonial rule felt frustrated and became obstructive.

Graduate Teachers’ Association: Triumph in negotiations.

Subsequent to my work on the back pay issue, senior civil servants invited me to serve on their committee to make representations to the Governor for Asians to receive the same special benefits (family allowance) as those given to Expatriates. This enabled me to become familiar with the Asian Senior civil servants. I benefitted from Kenny Byrne’s[1] advice, which went a long way to our founding the Graduate Teachers’ Association (GTA).

Nearly all graduates (except Hong Kong graduates), became members of GTA. However, only two Honours graduates were prepared to serve on the Management Committee. I had the impression that the reason the Honours Degree holders had devoted time and energy to obtain their Degrees was purely to earn a promotion. They were not interested in improving their ability to be better teachers or improve the education service. They wanted to be elite personnel in education, but preferred to have others in our Association do the hard work needed to get an improved salary and service conditions, while they reaped the benefits. In later years, when promotions by-passed them, they blamed others and resorted to backbiting and secret reviling. I should also note that Indian University graduates had no recognition in the service although they filled the big gap of Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry and Biology teachers, for which Raffles College and later the University did not produce enough graduates. They were conscientious and hardworking and deserved recognition.

[1] Kenny Byrne, was a Raffles College graduate, who established the Singapore Senior Civil Officers Association and was a leader of the union movements of government employees. He was one of nine Singaporeans appointed to senior civil service positions as the first step towards Malayanisation in post war Singapore. He served variously as clerk of the Legislative Council, Permanent Secretary Ministry of Labour. Later he resigned to contested elections and served in the first PAP cabinet. https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_77_2005-01-18.html

Demand for a revised salary scheme

Asian members of the Legislative Advisory Council had become aware of the discontent among teachers over salaries and lack of promotion prospects. They were demanding action by Government. Communist agitation had crept into the Singapore Teachers’ Union (STU). The Legislative Council appointed a Select Committee with C. C. Tan as Chairman to propose a revision of salaries for teachers and invited the STU to submit memoranda on the subject. I was not in the Singapore Teachers’ Union but as President of the Graduate Teachers’ Association, I sent a memorandum to the Committee.

C. C. Tan invited me to discuss it and I obtained insights into the workings of the Select Committee’s mind. They were against a unified scheme for all teachers. Instead, they favoured a scale in which each category of teachers would start at a different point and finish at varying maxima. However, all teachers could qualify on merit for promotion to higher posts including those in administration. I felt certain that the STU would insist on equality between all teachers, and would reject the scheme proposed by the Committee. Thus, the proposals for salary on which we worked so hard were doomed to fail. I was frustrated, and felt that some teachers were naive, others indifferent, some cynical, and some were just plain silly to allow communist leaders put pressure on Government to ask for the impossible. I suspected that the majority did not believe there would be any revision no matter who led them. Complacently, they gave their votes to the most vociferous leaders. Feeling frustrated, I decided not to waste any more time on this issue.

Radical Changes in the Education System.

A major event occurred in 1953. Sir John Nicoll, became Governor of Singapore in 1952, and breathed life into a new Education Scheme. I am proud to say I had a hand in it.

My role in the proposed Education Scheme.

As described in an earlier chapter, the PAP had formulated a new Singapore Education Scheme in the late 1940s, but the former Governor put it into cold storage. It included a new scheme of salaries and service prospects for teachers. The Singapore Teachers’ Union rejected it because it did not provide Trained Teachers equality with Graduate teachers. I heard from Kenny Byrne that Nicoll did not always accept the views of his senior assistants. He advised me to make an appeal to him to implement the shelved salary scheme.

An Appeal to Sir John Nicoll.

I drafted a letter of appeal and showed it to Howitt who was my Principal at that time. I wanted to gauge his reaction. In addition, I was the president of a trade union, and, in theory, could write directly to the Governor. However, I felt it would be courteous to send my appeal through the approved channels namely through the Principal, the Director of Education and the Colonial Secretary. However, there was a snag. William Goode, the Colonial Secretary, did not favour the scheme and probably would put a spoke in the wheel. Therefore, I decided to take the risk of bypassing him and making a direct appeal to Governor Nicoll, and fortunately, Howitt supported the idea. I feared the Secretary would return my letter and tell me to follow procedure. So naturally, I was vastly relieved and pleased to get a phone call from the Secretary saying that the Governor would see me with the secretary of my Union.

When my Union secretary and I arrived at the Government House, we felt highly honoured to find Sir John Nicoll himself waiting for meet us. On our way to the Governor’s office, he announced that he had decided to implement the shelved Education Scheme. We had coffee and spent some time getting to know each another. He asked my opinion on how the STU would react. I told him that I had obtained support from the current President of STU Choo Kia Song. He was pleased to hear that but remarked that he intended to go ahead with the scheme even if the STU rejected it.

Nicoll implemented the scheme in 1953.

“I felt that I had achieved the greatest success in my life: not merely for me but for my colleagues in Education.

The new Scheme, was more than a mere revision of salaries; it raised the status of Asian teachers, gave them equal opportunity with expatriates for promotion to administrative posts and introduced the element of merit for promotion without regard for paper qualification.”

Teachers’ reaction to the new scheme.

The vast majority of teachers appreciated my hand in getting the scheme implemented.

- Trained teachers were delighted.

- All would get better salaries.

- Principals of Primary Schools would be trained teachers and would get pensionable allowances; the ablest of them would get a promotion even over Honours graduates.

- Graduates, both Pass and Honours, studied carefully the published Education Scheme.

- Some had doubts and sought clarification.

- Some Honours Graduates who had not undertaken specialist teaching were disappointed that the appointment of Specialist Teachers was backdated to January 1950.

- Others were excited or even worried at hearing that Ince, the Chief Inspector had asked me to give him data about specialist teaching done in all schools. I understood the natural human fear that I might favour friends. I made it very clear that I would merely collate data. It was not for me but for the Principals to make recommendations.

- Eventually it transpired that almost every teacher who had taught Standard VIII and higher, received backdated Specialist Subject appointments. Four of us Raffles College graduates who did not have Honours degrees, received promotion to Superscale posts. The few Honours graduates who had obtained their degrees merely by studying books, without investing in improving their teaching in the belief that it would ensure promotions were frustrated when they found they would now compete with ordinary Pass graduates, Certificate and Trained teachers for managerial positions.

- Some expats were sore at having to work under Asians, but soon realised the culture had changed after the war.

At a personal level, a few of my colleagues became envious rivals and feared that the prominence that I had gained from the success of my appeal would help me to earn faster promotions in the service. I was sure they would hatch plots, as would the communist leaders in the Singapore Teachers Union.

As it transpired, two colleagues who I considered good friends were the ones who disappointed me as described in Chapter 16.