The reopening of English Schools 1945.

Immediately after the liberation of Singapore, a number of expatriate British officers, released from war prisons, set about reestablishing services. Cheeseman appointed the most senior graduate teachers, namely, N. I. Low and H. N. Balhatchet, together with Frank James, from the Aided Schools, to organise the English medium schools. They appointed S.C. Ting as Acting Principal of Raffles Institution (R.I.). The liberation forces occupied our school buildings. Therefore, we shared the buildings of neighbouring St. Joseph’s Institution (S.J.I.) Our (R.I.) school hours were in the afternoons.

The four-year war period caused students to lay off from schooling, and resulted in dire effects on most students. Many pre-war students did not return to school. Several students had died, or were in poor health or too old. Others lost the desire or incentive to study, and preferred to continue in jobs they had acquired. Understandably, many of those who returned had lost both the discipline and desire to study. Their command of English had weakened badly and they found it difficult to cope with their studies. We had fewer classes with smaller class numbers. The students and staff were extremely lethargic. For quite some time, we focused on getting the pupils into the discipline of learning. Much of our teaching was remedial. Teachers who tried to stick to the syllabus inevitably felt frustrated. Apart from the effects of the war and the Japanese occupation, the fact that we were guests in another school’s premises contributed to the lethargic spirit.

Sharing school accommodation caused problems

There was a history of rivalry between R.I. and St Joseph’s. Pre-war, there had been a fight between spectators from the two schools after a rough soccer match. Having heard the report of rough play that led to a fight, the respective heads of the schools had decided to suspend all soccer games between their schools. There had been no trouble during other games like hockey and cricket. In my opinion, if the heads had instead replaced the two soccer masters, then the students of both schools would have cooled off and the relationship between the schools would have returned to normal. Instead, even after the War, some of the pre-war students still remembered the unhappy relationship.

When R.I was allocated accommodation in St .Joseph’s, a graffiti war started between the students in a class of R.I. and one in St Joseph’s. The Brother Director of St Joseph’s, believing that R.I. had caused the problem, requested Ting who was the principal of R.I., to find us alternate accommodation. Ting was going to do just that. I believed in solving the problem mutually. One day, having ascertained that St. Joseph’s students had created graffiti during the morning session, I requested the afternoon R.I. class not to erase it. With Ting’s permission, I showed the Brother Director that the graffiti was not one sided. Having verified it, he suggested that the teachers in charge of the classes from the two schools take responsibility for stopping their pupils continuing the war of words. Thus, we continued to use the S.J.I. classrooms until the end of 1945 when the Monk’s Hill School building became available and we moved in there as a morning school.

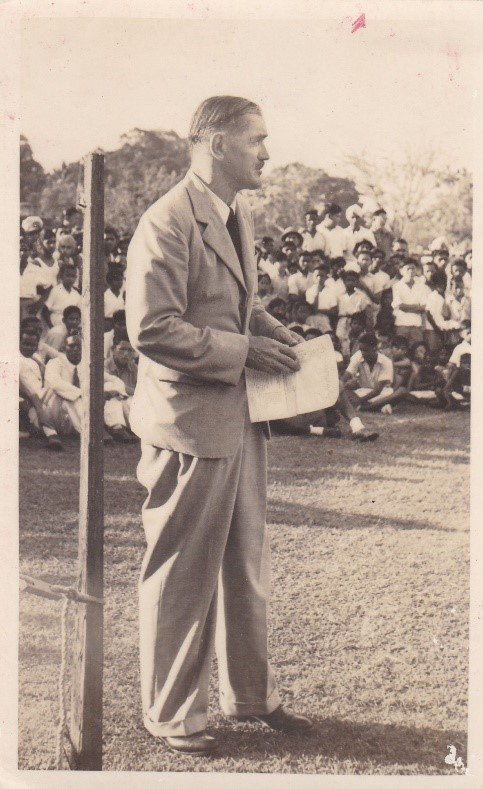

F.L Shaw rejuvenated Raffles Institution: 1946-49

In 1946 when we moved to the Monks Hill School premises F. L. Shaw took over as Principal of R.I. This was a milestone in my professional life. Shaw was of a different mould from most expatriate officials of that time, and I looked up to him as a model I should emulate. He treated all staff equally and enjoyed warm friendships with both Asians and Europeans. For example, he eschewed the practice of establishing two separate common rooms, appointing only expatriates as heads of departments and giving each of them the best classes to teach. He was very popular both as a person and as an educationist. I had known him briefly when I was in teacher training, and greatly enjoyed his sessions which involved lively and active discussions of Literature rather than mere recitation of dry facts.

Appointed as Principal, his first action was to pressure the authorities to expedite the renovation of our premises so we could return. He rapidly acquainted himself with each member of staff and learnt their strengths. Next, he set about reorganising the physical arrangements in the school as well as revamping the syllabus for each subject. For example, he created new space for science laboratories, and set up a common staff room for expatriate and local staff. Thus, for the first time, local staff had proper space for work and interaction. Shaw rapidly assessed each of his staff members, and allocated tasks. To my surprise, he allocated me the task of revamping the syllabus for English, although he himself was a specialist in that area. He wove himself intimately into our daily work. Unlike previous Principals, he assigned himself to teach English Language in a Standard 6 class[1] and Latin to School Certificate students.

[1] Standard 6 is the last year of primary education.

He supervised teachers closely, but no one complained. Occasionally, he reviewed the essay exercise books of every teacher of English, made suggestions or queried the approach being taken. For example, on one occasion, he asked me why I had started my School Certificate ‘D’ class, with the writing of simple sentences, proceeded to complex, compound, multiple sentences, and by the middle of the year reached only to two or three paragraphs. He feared that by the time the pupils sat for the School Certificate Examination, they would not be able to write essays. I showed him a set of exercise books the pupils had produced in the first weeks of the year. I had been obliged to correct almost every sentence. I argued that the students could not write essays unless they had a command of elementary syntax, could write sentences correctly, understand how to write paragraphs and how to divide an essay topic into sub topics. Otherwise, their essays would be haphazard. I assured him that by the beginning of the third term the class would be writing essays, and that nearly all the pupils would, at the least obtain a ‘Pass’ in the final examination. He looked critically at all the exercise books and remarked that in all his teaching career, he had never come across a school certificate class as poor in English as my D class. He realised that four years of Japanese occupation had destroyed the pupils’ English. He agreed that I was justified in resorting to remedial teaching and wanted to see its progress. Eventually he was pleased to note that three pupils from that class scored ‘A’ in English, none failed, and most scored credits. I am proud to say that several went on to become successful lawyers, engineers and teachers. Sam Sinnathuray who scored an ‘A’ became a High Court judge, and Tan Hwee Hock became a teacher at R.I. besides being an excellent water polo player and captain of the Singapore team that beat a powerful Japanese team. Lim Choo Beng became a top official in Singapore Airlines. That ‘D’ class of students went into the adult world without an inferiority complex. Teaching that class has been one of my greatest joys. I have worn their success in my heart like a gold medal set with precious stones!

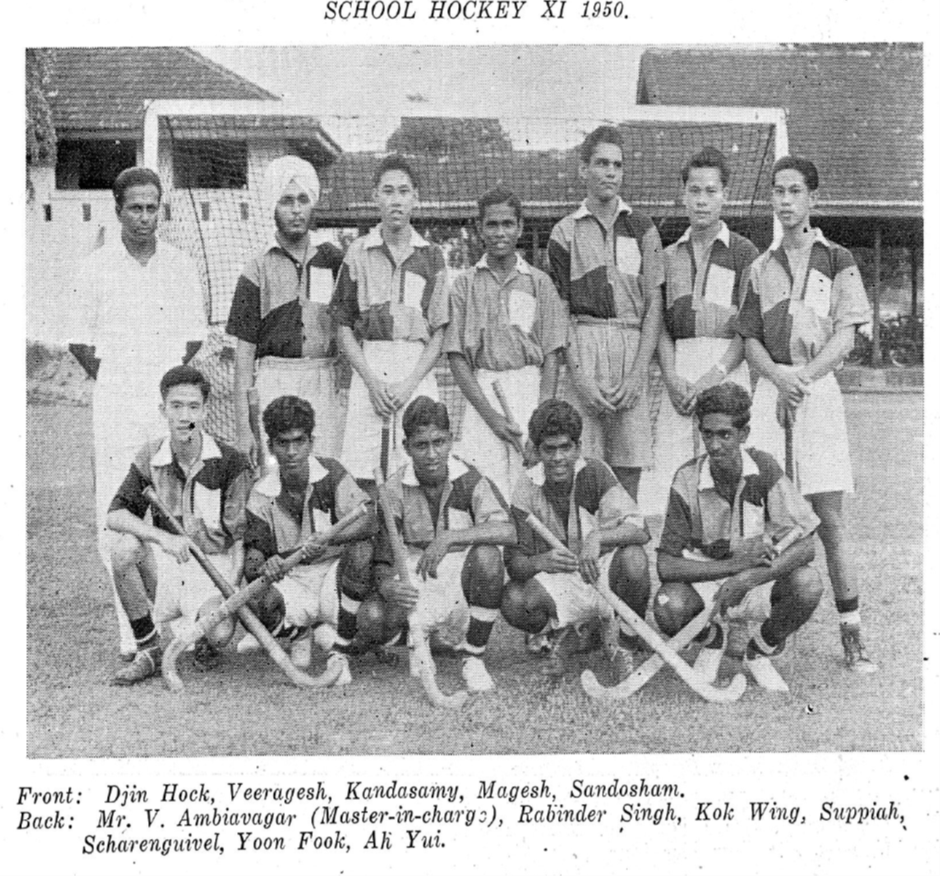

Sports activities

I started coaching the school hockey team soon after we moved into our own premises and Shaw arranged for us to use the Victoria School’s field on some days in the week. Shaw played badminton with his staff on Sunday mornings in the school hall. He was a good sport – he would always partner with one of the weaker players and enjoy his game even if they lost, and never blamed his partner for losing. He viewed it as an opportunity to get to know his staff better. He took an interest in our families and the progress of our children.

The legacy of F.L. Shaw

Within the short period of less than three years, he reorganised and re-established the school activities to their pre-war level. In addition, he gave us Asian teachers, a sense of equal status with the expatriates. In spirit, he gave us Malayanisation twelve years before it became an official fact!

He had to retire on reaching 55 years of age, and it was a great loss to education. R.I. would have benefitted greatly if he had continued for another five years. I take pride that the copy of his photo in the school hall was one that he signed and gave me as a personal gift. It is the only photo that has a signature!

F L Shaw

A warm hearted friend;

A great gentleman;

A modest individual;

An expatriate sans colonial complex;

A great principal;

An excellent teacher;

He was my teacher, my principal, my mentor, my friend. He made me feel colossal!

If it is true we come back into the world again, I hope we meet again

V. Ambiavagar

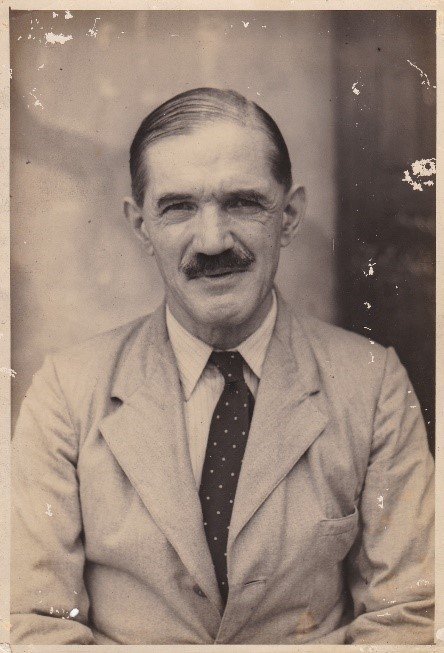

E.H.Wilson succeeds Shaw in Raffles Institution (1948-51)

In February 1948, Wilson assumed office as Principal of Raffles Institution. He was gregarious and affable. He had served in World War One. While teaching or administering education in the Malay states he had been an officer in the volunteer forces and a prominent sportsman playing Rugby, Cricket and Hockey for Malacca and the Negri Sembilan. Thus, he had considerable social contact with Asians, and displayed no colonial snobbery. Indeed, he enjoyed playing doubles tennis with us, always partnering Low Kee Pow, the best player among us, and winning.

However, under him, I felt that the discipline in school and of dedication to teaching declined. I noted that some teachers fell into the habit of being late for school and being tardy in returning to their classes after the recess and free periods.

Unlike Shaw, who used to review the essay exercise books of all classes, Wilson did not. He did walk around the school daily to keep a watchful eye on pupils and staff. However, he did not go into a classroom or pull up slackers who deserted or neglected their classes. Most teachers were dedicated but not all. For example, a couple of the new expatriates and an Asian teacher reduced the frequency of assigning written work, or did not mark and return it. Another neglected his class while he busied himself studying for his own London University External Examination. Wilson told us, his tennis companions, about such lapses. Wilson’s approach was to take note of the teachers who had irregularities as well as teachers who were dedicated workers, and base his recommendations for promotion on such assessment. For example, when posts of primary school principals fell vacant, he recommended only dedicated teachers for promotions.

Wilson instituted a policy of giving automatic promotions to students even if they failed their final examination. This adversely affected discipline, particularly since there was no remedial teaching for weak students. By the time he retired, one class of Standard VIII (Secondary Three) consisted entirely of students who had failed.

However, on the sports field, discipline was good. Pupils knew that he would use the cane. He took measures such as hiring a ‘sit-on’ mower when ground staff reported that the mowers were out of order. His presence at all inter-school games and his comments promoted the standard of all team games, increased the enthusiasm of sports teachers and the discipline of both players and spectators. In my opinion, if Wilson had also pulled up teachers who were not towing the line in teaching and had instituted remedial teaching for sub-standard pupils instead of giving automatic promotion to failures, he would have been an ideal Principal.

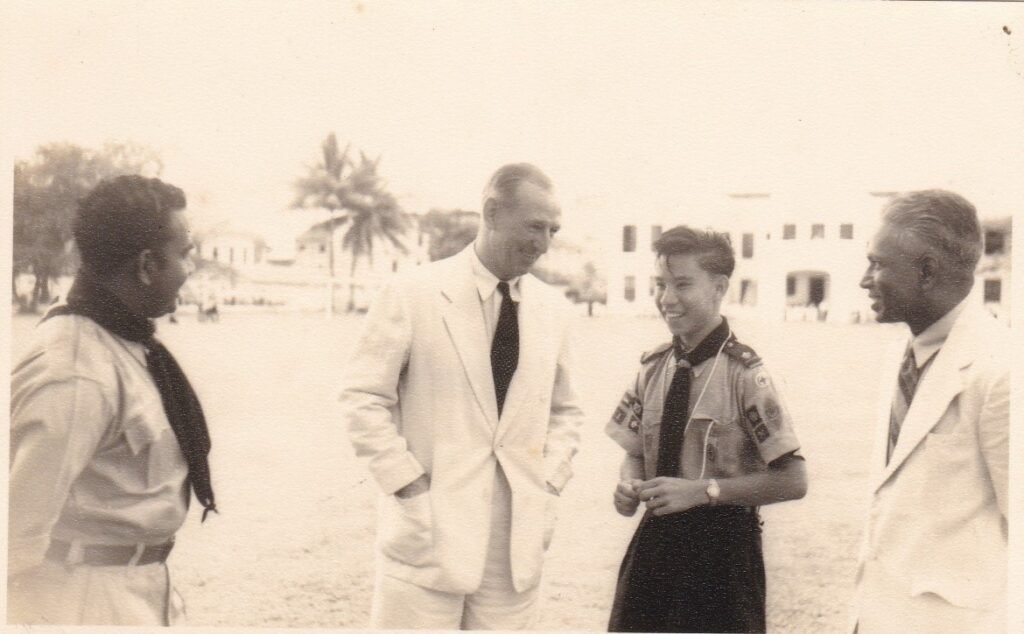

P.F. Howitt Principal of R.I (1952)

E.H Wilson retired in 1951, and Howitt was appointed Principal of R.I. but he was on long leave. At that, time there was no official position of senior assistant to the Principal. Unofficially if an expatriate officer was not available, a senior Asian graduate with either an Honours or Pass degree assumed the responsibility. Initially Ralph Ellis was Acting Principal until he moved to the Department of Education, and named Wee Siong Kang Acting Principal. I felt that thedecline in discipline continued under the “acting” regimes of Ellis and Wee.

In 1952 Howitt assumed his position as Principal. He discussed with the senior teachers, the problems we thought needed attention. I shared my view that discipline among a few teachers was lax and that automatic promotion of students who failed their examination had adverse effects on the school. He promised to look into both. I heard from colleagues that a particular new teacher appeared to be unbalanced in his behaviour, throwing books at pupils and using four letter words. I suggested they draw Howitt’s attention to it, but they wanted me to do it. I thought it would be better for Wee Seong Kang to do it since he had recently acted as Principal. However, he said that he could not bring himself to break the man’s rice bowl. He was indeed soft hearted and allowed his heart to rule his head. I felt the man’s conduct was harmful for his pupils and that schools existed to educate pupils not provide rice bowls for teachers. I brought the matter to Howitt’s attention and he passed the problem to the medical authorities who sent that teacher to Woodbridge[1].

Howitt dealt with other problems. He reprimanded a teacher who spent his time studying for examinations instead of teaching his class, and made it a rule that teachers would have to get permission before leaving the school premises. He announced that he would superannuate all over-aged pupils who failed the end of the year examination.

I was the de-facto teacher in charge of English, and he requested me to draw up the syllabus and set the examination question papers. However, he personally checked English Language exercise books of all classes, including mine. Although he did not delegate the responsibility of checking, Howitt requested me to ensure that all teachers of English set a minimum amount of written work, and that they marked and returned the books. I sent a note to all teachers of English asking them occasionally to submit to me samples of written work so I could check progress. One Asian and one expatriate teacher protested. Howitt explained that this was necessary to ensure a uniform minimum standard of written work in all classes so that pupils would be able to cope satisfactorily with English Language in their School Certificate examination. To my surprise, Howitt requested me to be his unofficial senior assistant instead of Wee.

However, before Howitt could firmly re-establish discipline and an atmosphere conducive to learning in Raffles Institution, he gained a promotion and moved to the Department of Education.

[1] Woodbrige was the hospital for the mentally ill.

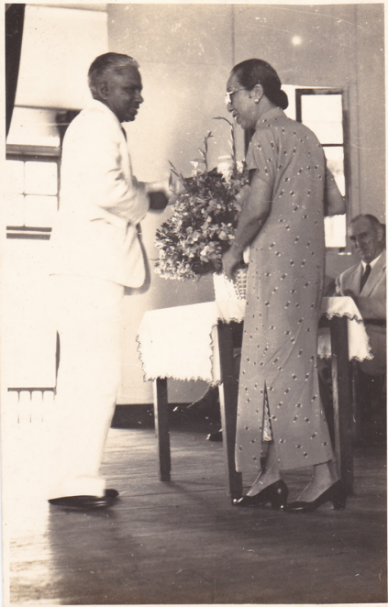

L to R. Wee Siong Kang, Unknown, David McClellan Director of Education, Ambiavagar, P. F. Howitt

Prior to the new Scheme of Service (see next chapter), seniority in service was the determinant for promotions, except that every expatriate from the first day of his service was senior to all Asians. Shaw had ignored this policy in designating heads of specialist subjects. The old order of seniority was under threat. Competition among the Asian teachers for the few available senior positions was extremely fierce. Some would use any means at their disposal to gain an advantage. The post of Principal of R.I was a plum post.

For example, a colleague created justification that he should be given the position of Principal on the strength that he was an Honours graduate, although he and I qualified in the same year. He managed to convince the authorities in the Department of Education Ministry and was made acting principal in June 1953. I argued that that new Salary Scheme abolished the superiority of Honours graduates over those with a Pass. Some employment records from the early years were lost. I had considerable difficulty in getting statements from relevant officers to show that I was a qualified teacher in 1928 already in the Education service, when I entered Raffles College. This made me senior to those like him who graduated from College at the same time as I had, but became trained teachers and entered the Education service only after graduation.

I gained the appointment in November 1953.

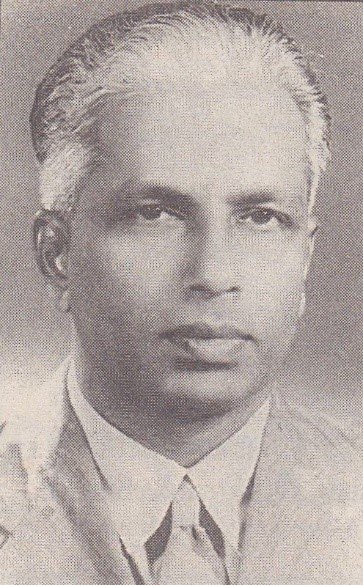

Acting Principal Raffles Institution, November 1953 – March 1955

On Howitt’s recommendation, I became acting Principal when he was promoted to a position in the Ministry. My 16-month sojourn as Acting Principal was unusually long. It was the practice at that time to announce the name of the person who would be promoted to Principal R.I in anticipation of the retirement of the incumbent. The announcement said that John Young was to be transferred from Malaya and promoted to the position. I expected him to take over the position immediately since most acting positions lasted only a few months. However, he was placed in the Ministry as acting Deputy Secretary, and I continued to occupy the post of Principal Raffles Institution for a substantial period.

My personal conjecture is that several factors caused this manoeuver. Political pressures to expedite Malayanisation increased. The position of Acting Principal was usually reserved for expat officers. The authorities wanted to see whether a local officer could command the respect of the teachers with whom he had worked for many years, as well as garner the respect of students. It was to be a test of my calibre. I wholeheartedly welcomed the challenge.

I suspect that I was selected in recognition of all the effort I had invested in sports and the Chorus magazine in addition to my regular teaching duties.

I expected that many colleagues, particularly Honours graduates who had been in service longer than I would be envious and disappointed. At least one colleague could not contain his chagrin. He called me and said, “Congratulations, you have played your cards well.”

“Thank you!” I responded and astutely added, “Unlike you, I don’t let others see my cards.”

Reclaiming discipline

My top priority was to re-establish the discipline that had prevailed from McLeod’s day to Shaw’s and contributed to the reputation of the school as Singapore’s premier school.

After consulting Howitt, I announced that students who failed the Secondary 3 examination and were too old to be retained would have to leave school. At the end of 1953, I was able to excise this contributor to the cancer of indiscipline. If they had remedial teaching early in their school life this problem could have been prevented. I was sorry to send them out into society where they probably would be troublemakers. The majority of staff supported my action.

Instilling discipline in secondary school is a delicate task. The basic approach I used was to determine the underlying causes of the particular problem, and try to adapt the solution accordingly. Furthermore, I ensured that the punishment would not humiliate the miscreant, but rather impress on him that he what he had done was unacceptable. As Principal, I faced different types of challenges related to discipline. I recall three examples:

- A teacher complained that his pupil was uncontrollable. He was the youngest in the class, yet finished his assignments ahead of everyone, and wandered around disturbing the class. At times, he brought small snakes and released them in the classroom. His classmates reported that after school, he would release his Alsatian dog on them. I advised the teacher to set the boy varying challenging projects such as a difficult problem in mathematics or writing an article for the magazine to keep him occupied. On interviewing the boy, I found that he was the elder of two children whose parents worked all day. When they returned they gave all their attention to his young sister. He played tricks on his classmates because they teased him. I called his father for an interview and pointed out that his gifted son craved for parental love, attention and guidance. His parent took note of my advice and the boy caused no more problems.

- The head of Raffles Girls School complained that a magazine produced by one of my senior classes was libellous about the relationship between a pupil at RI and one at RGS. She sent me a copy. On investigation, I found that the editor of the magazine had written it himself and had not obtained approval from the teacher in charge. His excuse was that he wrote it at the last minute and was short of time. It was a serious offense. I rejected his excuse, and made him recall all copies of the magazine. I considered the various options for punishment and decided to relegate him to the “B” class although his academic performance entitled him to the “A” class. He would study the same subjects as in the A class, but lose the status symbol. He appeared to accept the punishment, but a couple of days later, a prominent lawyer came to see me about it. When I gave him the particulars, he appeared to understand. Subsequently, the Deputy Director of Education called. The boy’s father had met him socially and given him a garbled version of the issue, and requested his intervention. I told him the full story. He agreed that my disciplinary action was appropriate and told the father accordingly. The father asked whether he could transfer the boy to another school without having an adverse comment on his leaving certificate. I immediately provided him the leaving certificate without any adverse comment on his conduct.

Another example, relates to the son of a friend who was a doctor. He was a very intelligent lad, and was an outstanding all-round sportsmen. However, being too involved in sports, he failed to qualify for a place in the classes that had subjects that were required for entry to medical school. My friend wanted me to waive the criteria and make an exception for his son. I liked the lad and felt very sorry for him, but in all honesty, his results were too poor for me to grant a favour. I kindly suggested the best solution would be to let him repeat Form 3 and limit his participation in games. The father would not accept that and stormed out in anger. Later, after a few drinks, he called me over the phone and threatened to beat me up! I invited him to do so and be happy about it. Subsequently he got the boy transferred to another school for a place in the requisite class. The boy brought sporting glory to that school, but did not qualify for a place in medical school. In addition, I lost a friend!

Dealing with teachers.

Another challenge came from teachers. Although most of the teachers accepted my authority as Acting Principal, a few tried to take advantage or refused to accept the authority. Two of them gave me trouble. The first had come to R.I in 1950 as a Trained Teacher, rather than a graduate teacher, because his qualification from an Indian university was not recognised. He obtained a recognised Masters degree two years later. We had became friends when both of us were teachers. When I assumed the Acting Principal’s job, he requested that I make him a specialist teacher leapfrogging over Wee Seong Kang, who had been Senior teacher for History since 1931 in R.I. would be eligible to get his specialist appointment backdated from January 1950. I refused and tried to explain that the terms of the new Scheme of Service allowed for appointment of specialist teachers be backdated to January 1950. At that date, he was not recognised even as a graduate teacher. He was disappointed that I did not support his desires and became hostile towards me and set about to make me look unfair and unreasonable. He went on to complain to the Ministry that I assigned him unreasonable teaching assignments. Ignoring my explanation for the tasks, he appealed to Howitt (who was in the Department of Education) for a transfer to another school, citing his reasons. The Department investigated my reasons and supported my stand and he had to continue serving in R.I.

The other teacher who gave me a problem ignored my directive that all teachers should be punctual and not leave the school premises without prior permission. He sent me a letter objecting to the rules I imposed and stated that he was requesting the Department for a transfer. I knew that was foolish since it would ruin his chances of promotion. However, the Department did not answer his letter, and he continued in R.I.

I wish I had not been obliged to deal somewhat harshly with these two colleagues, but I had no choice. Letting them off lightly would have made me look weak and there would have been more and more indiscipline.

Yet another teacher who expected a favour since he was a friend had opted to remain teaching in a Primary school so he could study and become an Honours graduate. I was President of the Graduate Teachers’ Association. He wanted me to appeal to the Governor to give him priority in a promotion for Honours graduates. I told him to write and sign the appeal himself, and I would forward it. Personally, I thought the time for such appeals was long past – it should have been made to the Legislative Council before the scheme was gazetted, but the Honours graduates were asleep at that time!

A different type of challenge arose from a dedicated Physics teacher at a time when the Education service was very short of Physics teachers. He resisted pressure from his family to resign and manage prosperous family business and even gave weak students free tuition in the afternoons. However, he had a bad habit. During practical sessions, he would withdraw to an adjoining room to smoke, while keeping an eye on his students. When I spoke to him about it, he said he was sorry for his addiction but assured me that he always kept an eye on his students. I had to do a balancing act between what was good for the school and for education versus straightforward disciplinary action. I decided for the former. After John Young took over the school, he reprimanded him for his habit. He was so upset that he resigned immediately and went into his family business. His abilities and character were later so appreciated by Government that it appointed him Chairman of the Public Services Commission. That made me feel vindicated.

Introducing new features in Raffles Institution.

I pioneered the establishment of Post School Certificate classes. At that time, neither the University nor the Ministry of Education suggested the introduction of pre university classes for students who faced a yawning gap in knowledge between the Cambridge School Certificate examination and the University Entrance Examination. To help our pupils, I discussed with relevant colleagues the possibility of voluntarily conducting a three months course, at Post School Certificate level, during our free periods. They agreed to do it. Thus, I pioneered the Post School Certificate classes in Singapore. In 1953, the school presented two candidates for the University Entrance examination and both passed. One of them, Mahendran, my eldest son, won one of the two Entrance Scholarships awarded to the two top candidates and went on to study Medicine.

A year later, the University announced a four- term Pre-University (Pre-U) course before sitting the University Entrance Examination. R.I. had already pioneered the class and we were able to set up two classes and presented them for the Entrance Examination in 1954. My daughter Indra joined one of the classes, won a University Entrance Scholarship as one of the two top performers, and went on to study medicine.

There was much criticism of the University’s policy because medical students would spend four terms after their School Certificate in a Pre-U class and subsequently spend one more year at the University in a Pre-Medical class. In contrast, students in the U.K. could sit for the Higher School Certificate Exam two years after their School Certificate, and go straight into medical studies. It took the University Council a few years to accept this procedure and to scrap the Pre-Med year.

Physical education and uniformed services.

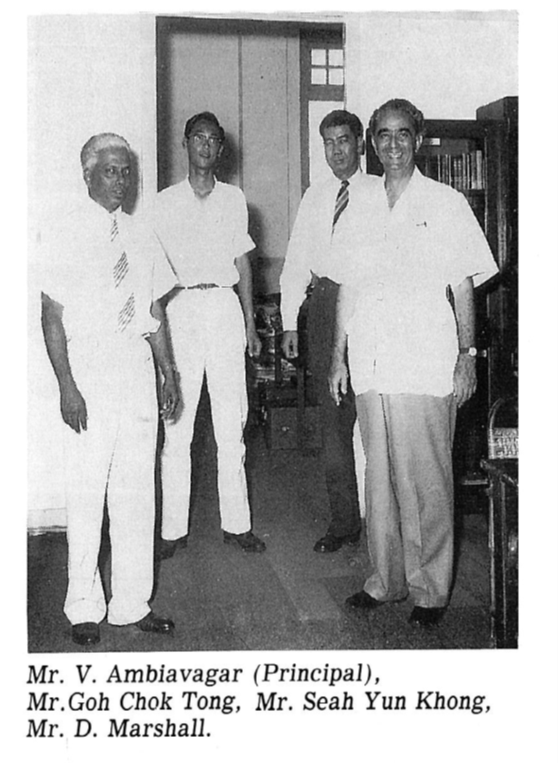

Another innovation I introduced was to upgrade physical education so that all year groups participated. In order to do this, I revamped the school field to accommodate soccer and hockey simultaneously, and revised the after-school schedules to increase the number of hours for team games, while reserving time for coaching in athletics. With an enthusiastic Seah Yun Khong, we revived gymnastics and judo, while Philip Liau produced lively plays with his drama society. I excused pupils who had genuine grounds for opting out of these activities, and provided lunch for those who could not afford to buy lunch to stay on for sporting activates after school hours. Teachers ensured that pupils went home immediately after games and did not loiter in the premises. I was present every evening. I enjoyed watching the pupils at play and encouraged their participation. I was very pleased to note that several teachers joined me voluntarily.

Source: The Rafflesian. Volume 24. November 1950

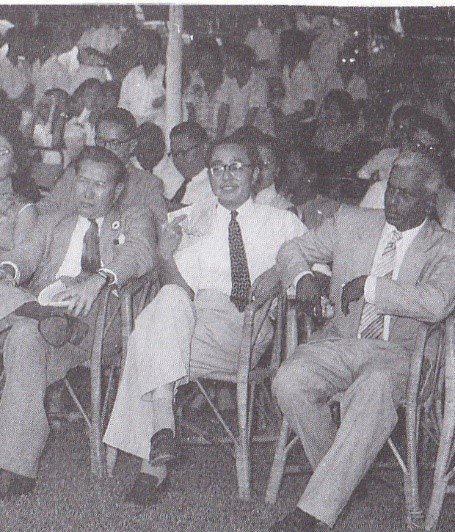

Old Rafflesians Hoffman (Editor in Chief, Straits Times), Gwee Ah Leng (Senior consultant physician) and Ambi at a school function.

Source: E. Wijeysingha. 1962. The Eagle Breeds and Gryphon. Pioneer Book Centre. Singapore.

Goh Chok Tong (later became Prime Minister), Seah Yun Khong (later became Principal RI), David Marshall (Chief Minister of Singapore)

Source: E. Wijeysingha. 1962. The Eagle Breeds and Gryphon. Pioneer Book Centre. Singapore.

The Red Cross Unit of 40 was enlarged to 97, officially enrolled, uniformed, and instructed in First Aid. 37 completed the course, sat the First Aid Examination and passed. The Scout troops that had only one Scout Master now had five.

For the first time in the history of the school, a Youth Rally of Cadets, Scouts, Sea Cadets and Red Cross Cadets, over 400 in uniform, was held for parents to witness a display of what their sons learnt in these organisations.

School Assemblies and Speech Day

Another activity that I revamped was the weekly School assembly. Instead of two separate assemblies, one each for the lower and upper schools, I re-organised the hall space to enable us to have a single assembly, and changed the content from the stereo type announcement of results of games and reminders of rules. Instead, I invited teachers, prefects, prominent pupils or guests to address the school for not more than 10 minutes.

Speech Days were historic and spirit-warming occasions, yet the lower half of the school had been excluded due to space considerations. I managed to ensure that the full school could attend by using the canteen and the row of classrooms on both sides of the hall, wired for loud speakers to bring the speeches from the hall. The pupils seated there would not see the proceedings on the stage but would witness from vantage points, the V.I.P. guests arriving and the Guest of Honour inspecting the Guard of Honour, in addition to hearing the speeches and the names of the prize-winners as they were announced.

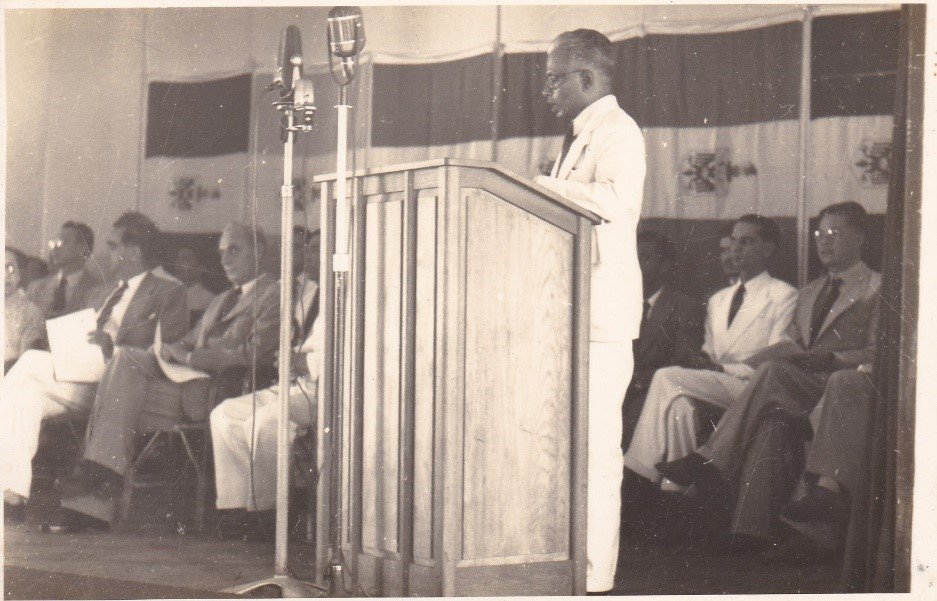

Raffles Institution Speech and Prize Giving Day, 1954

The Speech Day was one of the highlights of my time an acting Principal. Sir John Nicoll, Governor of Singapore was guest of honour. David Marshall, President of the Old Rafflesians Association presided. Dr. Lim Boon Keng and R.M.Young, Director of Education, were the V.I.P. guests. Mrs. Lim Boon Keng gave away the prizes.

Standardised marking for examinations

I think I made a significant difference to academic standards through my efforts to standardise the marking of examination papers. This contributed to the school’s image. In the past, Principals had accepted without any vetting, the marked final term examination papers. I knew that the award of marks especially for the Essay paper varied too much from teacher to teacher; some were too strict, others too lenient. I discussed privately with separate teachers, and agreed on criteria for marking and setting standards, and made it the responsibility of the teachers in charge of special subjects to check the questions and the marking, to ensure uniformity and standards linked as closely as possible to the Cambridge Examinations Syndicate.

The Effects of Good Discipline.

The measures for improving school discipline that Howitt began and I continued with his backing from the Ministry until February 1955 demonstrated visible results. The 1954 School Certificate results were better than those of many preceding years, and John Young who became the next substantive principal of R.I gave me the credit for it in the 1955 Speech and Prize Day. In 1954, my pupils Hwang Peng Yuan and Colin Leicester were the first to win the Queen’s Scholarships since 1938. Mah Guan Kong and Lim Pin followed them in 1956 and 1957. All four Queen’s Scholars were true blue Rafflesians, not merely scholars from other schools who had attended a Special Queen’s Scholarship class that was housed at Raffles Institution. After 1957, the Queen’s Scholarships were replaced by the State Scholarships. I think that the four winners of the Queen’s Scholarships were helped by the disciplined tone of the school and the dedicated teaching they received from all their teachers.

I think that in succeeding years, all pupils at the school benefitted from the discipline which Young also maintained after me. The real purpose of attending school permeated the minds of most pupils. Even some teachers who previously had been merely ‘performing duties’, derived pleasure in giving of their best. The school continued to produce distinguished achievers like Goh Chok Tong, who rose to be Singapore’s Prime Minister, and Tommy Koh, who became ambassador to the United Nations. They continued to pave the way for Raffles Institution to establish a glorious future. We need to remember that, contrary to popular opinion, Raffles Institution did not get all the best pupils from the government Primary schools. Some were directed to Victoria School, and some years subsequently, the placements were on a regional basis and there was no common examination for entry to secondary school.

Therefore during those earlier years, Raffles did not admit the best pupils, employ the best teachers, reduce the size of classes units and introduce special amenities in order to achieve good results. In fact, the school lost quite a few experienced teachers either on promotion to become heads of other schools or to serve in newly established schools. Thus, R.I. was at a disadvantage in comparison with the Aided Schools who maintained their identity because their staffing remained constant.

John Young as Principal of Raffles Institution – confusion of historical dates

Latter-day authors like Wijeysingha incorrectly stated that “John Young took over as Principal from Howitt on 28th February 1954 and was to remain in that position up to 1957. Ambiavagar had acted as Principal in between and left as headmaster of Beatty Secondary School on Young’s return.” In fact, I took over from Howitt in November 1953, and was Acting Principal of R.I. until February 1955, when I took up the promotional post of Principal Beatty Secondary School. A delay in finalising promotions and appointments caused the confusion in dates. The delay arose out of a controversy between the elected Chief Minister, David Marshall, the expatriate officials, the Governor and the Colonial Office over continuing the existing colonial practice of promoting junior expats over the heads of more senior Asians, and the need to implement Malayanisation of posts and promotions in accordance with the new Education Scheme. It was only early in 1955 that a compromise was achieved. One aspect of the compromise was that John Young received a back dated promotion. In other words although he did not take up the post and move to Raffles Institution until February 1955, he was retrospectively given the salary of the Principal from February 1954.