I begin a graduate programme but the scholarship is a pittance

I responded to a circular inviting applications from trainees and teachers for indentured scholarships for a Diploma in Arts or Science in Raffles College. I am ever grateful to my two friends, T.E.L Retnam and Ben Dudley who signed my guaranty form.

However, shortly after I gained admission, I almost renounced the scholarship. Three factors worried me. Firstly, I learnt that although our syllabus was wide-ranging, it would not prepare me for an external degree from the University of London. In order to obtain a University degree, after finishing Raffles College, I would have to steal time from my teaching, and pay scant attention to extramural activities in order to study for that examination. I did not want to do that.

The second shock came at the end of the First Term. I learnt that I would not be getting my salary of $130. I would have to subsist on the $50 scholarship, of which $30 was deducted for hostel accommodation and food. Where was I going to find the money for books and other expenses? Should I renounce the scholarship? I mentioned to Dudley and Retnasabapathy that I was thinking of rejecting the scholarship. They offered to cover my share of the mess bill until I graduated and agreed to wait for me to reimburse them eventually. I was very touched, and accepted the offer. However, more news that is unfavourable followed. At the end of the first year, the authorities informed me that the full scholarship was only for term time. I would be paid a lesser amount during the long vacations because the Government assumed that I would be staying with my parents or guardians. I had neither! I could not afford to withdraw because I would have had to refund the first year scholarship. Therefore, I bravely continued, and practiced frugal living – walking a long way to college and not buying clothes or shoes for the entire two years. I had only one pair of shoes, and on one occasion, the sole gave way midway through a walk in rain. I tied it back as best I could but struggled and unfortunately reached home barefoot. That night I bought a new pair of sneakers for $1.50 and used it for the entire final term.

The third shock came when I learnt that Government was postponing the building of the second hostel because of the worldwide economic depression. Second and third year Singapore students would not get hostel accommodation and would only be paid a meagre $25 per month as scholarship allowance. Since I was a qualified teacher, if I had been working, I would have earned $130 per month in the first year, $140 in the second and $150 in the third plus a 15% cost of living allowance. When I graduated from Raffles College, I would be paid only an additional $50 allowance per month for my Diploma. It would take me more than 10 years merely to recoup what I would be sacrificing. (As it happened, in 1931, when I graduated ,the 15% allowance was stopped.)

I was sorely tempted to leave College and return to teaching, but an unseen power or an obstinate streak in me prevented me. In retrospect, I am proud and happy that I continued the course at Raffles College. My Diploma enabled me to gain great satisfaction in overcoming challenges at work and extra mural activities, and get promotions later in my career. It enabled me to teach in secondary school, which was more challenging and satisfying than teaching primary school. My own experience in my teen years and that of my contemporaries enabled me to appreciate the problems of growing up and adjusting to life.

University education – is it worthwhile?

The words of Phillotson to Jude in Hardy’s Jude the Obscure express my sentiments: “You know what a university is and a university degree? It is the necessary hall-mark of a man who wants to do anything in teaching.”

The average person seeking higher education is ambitious for wealth, position, prestige, luxuries or an influential marriage, but frequently fails to secure contentment and happiness, and flounders in unpredictable ways. Higher education made me the best possible teacher I could be, and enabled me to derive great joy in my work. I looked upon work as a surer means of happiness through achievement while earning a living. No one could take away the visible evidence of the progress of my pupils. Tertiary education gave me the mental make up to achieve my ambition and fortuitous circumstances propelled me higher than my dream.

Years later I read, with pleasure, Swami Vivekananda, “Work, to give service, is also religion”. Mahatma Gandhi said that man should give “selfless service and remain free from the taint of egoism”. In my own way, I aimed at a high ideal in work. I wanted to teach to earn my living but while doing that the monetary reward would be secondary to doing my best for my pupils; their progress should be a greater source of happiness than the material benefits. Teaching was not my religion and I was not practicing renunciation. However, my sights were not on amassing wealth or gaining advancement. In life, I actually did not amass wealth.

Reflections as a member of the Raffles College pioneer class of 1928

I was one of the pioneer batch of students recruited in the newly founded Raffles College. Like most pioneer batches, we faced several issues – financial and educational. The next few paragraphs include my reflections on those issues. It is worth reiterating that this was during the British colonial era. In addition, my experiences straddle 1929, the year of the big international financial crisis.

Raffles College was founded initially in response to a demand for teachers in secondary schools. At that time, the British Colonial Service exploited Singapore and other similar territories. Top civil service and professional posts were reserved for expatriate British, Australian and New Zealand staff. They received outrageously high wages, frequent long leave with full wages and paid passage. Simultaneously, local citizens did not have access to tertiary education. Additionally, the few local citizens who obtained British university qualifications had much lower wages than their expatriate counterparts, and were not eligible for paid overseas vacation. (Table 1)

Table 1: Comparative Wages schemes of expatriate and locals with the same qualifications (1928 – 1933)

| Expatriate | Local with the same qualification from a UK university | |

|---|---|---|

| Medical doctor | $400 – $800 + paid overseas vacation | $250 – $400 No paid vacation overseas |

| Graduate teacher | $400 – $800 | $130 – $300 |

Throughout the years, the Colonial establishment strongly resisted the idea of establishing local universities. The Establishment had an underlying fear that the need for expatriate personnel would decline if the services were opened to local citizens. For example, the first local Medical School (later named King Edward VII College of Medicine) was established in 1905, only when an adequate number of white doctors could not be recruited to staff hospitals in Singapore and Malaya. However, its graduates earned only a licentiate not a medical degree. Similarly, in 1928, Raffles College was founded after a long period of resistance to local demand for the local training of qualified secondary school teachers, and graduates earned only diplomas and not degrees.

The average Asian teacher was an economic immigrant to the country and therefore accepted with resignation, even gratitude or servility the unjust difference. Some expatriates like Holgate, Shaw, Purcell and Professor Gillett sympathised with Asians and dealt with them as equal human beings. Thus, they won our respect.

The curriculum

Theoretically, the curriculum for the College was to suit local conditions and needs. If that was so, I failed to see the rationale for ignoring the English Language and placing extremely heavy emphasis on English Literature from Chaucer to Blunden. Certainly, this did not prepare us to teach Secondary school. Scottish Universities had English Language, but not us! Latter day historians documented in a Souvenir magazine that that “During the whole of the Raffles College period, Language and Literature were taught together.” “Language study consisted of Composition and prose style and Precis writing in the first year, while second and third year courses dealt with metre and the history of criticism.” I regret to say that there was no study of Language, no essays or precis-writing or history of criticism. It was only during tutorials for students who chose English Literature as their principal subject, that tutors commented on style in prose and verse, metre and literary criticism. The Raffles College souvenir provided am attractive description of the syllabus for English Language. If the teaching had reflected the contents of the souvenir, it would have been very beneficial. Instead, the teaching we had appeared to aim at minimising the number who would graduate from the College, thus illustrating that Asians were unable to master the English language, and would not be able to replace expatriates as teachers in Secondary Schools. The curriculum appeared to be designed to prevent us attempting the External London University examinations.

In 1956 when I appealed to the University to introduce English Language, I was ignored.

The 1928 intake had 42 students. Mr Richard Winstedt Director of Education directed his staff to select students based on the School Certificate results. H.T Clarke, Inspector of Schools, Singapore, ignored the directive. Instead, he gave preference to qualified teachers and those in training. The wisdom of his selection criteria became evident when of the 12 from Singapore; only one of those selected by him withdrew, as did two of the four private candidates. All those who remained graduated. In contrast, of the 30 candidates from the Malay states, 11 withdrew within one month, and only 16 graduated. We had the choice of an Arts or a Science Course. The Arts Course offered English Literature, History and Geography; Science offered Chemistry, Physics and Mathematics. Every student had to do one subject at principal level and two as subsidiary. The principal level students attended weekly tutorials; in Literature, we read long critical essays on authors, or works, listened to comments or discussed points we had made or missed out. In addition, indentured students (those with scholarships from the Education Department) did Education, which involved practical teaching in schools during two long vacations.

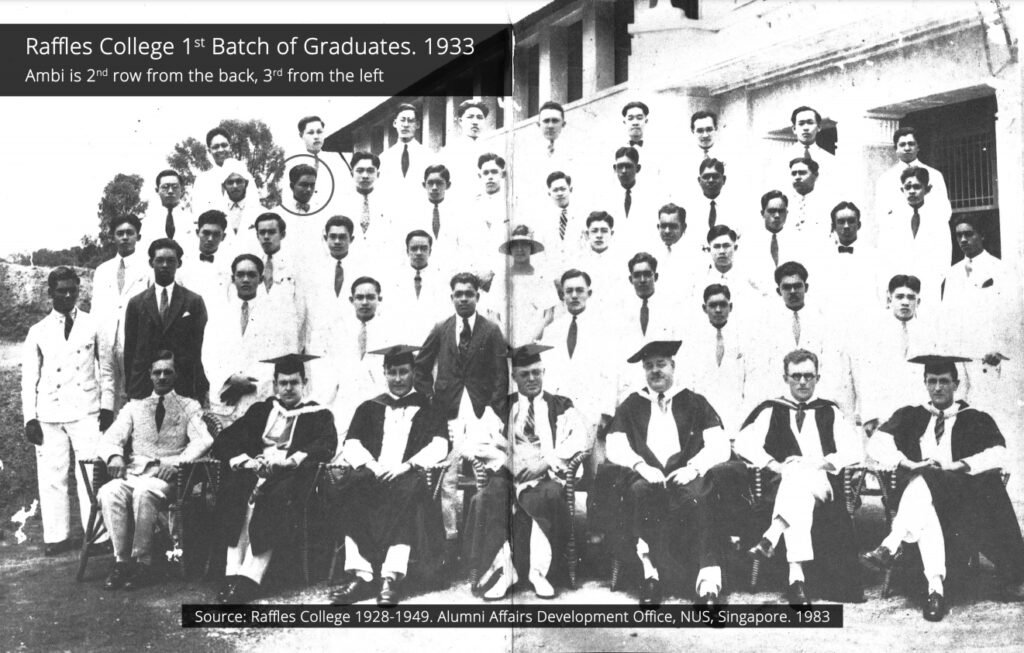

Of the 42 who gained admission, only 28 passed the final examination and that too, because at the last minute, the criteria for graduation changed to allow even those who failed a subsidiary subject to graduate.

It took 10 years before the 1938 McClean Commission identified that the Secondary School education in Malaya leading to the Cambridge School Certificate Examination was not sufficiently high to qualify candidates for university education and recommended at least a year’s extension of secondary education prior to admission to tertiary education.

Academic and life experiences in Raffles College

I was fortunate that I had the three-year course in teacher training prior to Raffles College. Even so, I had to sit up late every night to read for my weekly thesis. Although the extensive syllabus from Chaucer to the war poets was frightening, many of us guessed that for examinations we needed only to concentrate on certain periods, writers and aspects of literature. However, we did read a great deal for our tutorials. We had several tutorial essays on them and questions on them appeared in one of the three examinations we sat.

When I sat for my first year examination, my mind blacked out and I could not answer the first paper. I did the re-exam eight weeks later. It was shocking to realise that 48% of students who entered Raffles College between 1928 and 1938 failed. I would have been among the failures but for the three years in teacher training classes.

However, some graduates showed they were not inferior to graduates from prestigious universities. Many of them became the leaders who established Singapore and Malaysia as stable, successful, prosperous and happy nations, with minimum corruption and a source of admiration by older nations.

The administration block, which had a hall, was not utilised until June 1928. Lectures in English, History, Geography and Education during the first term were held in the house intended for the Principal and the tutorials were in the homes of professors. Lectures and tutorials in Chemistry, Physics and Maths were held in the Science block. All undergraduates, except two female students, resided at the hostel.

The Principal of the College, Dr Richard Winstedt had several other concurrent responsibilities, hence was principal only in name. There was no Principal’s office. Not surprisingly, few records were maintained and this has proved to be a challenge for latter-day researchers. The professor of mathematics deputised for the principal.

Hostel life, although restricted to one year only for Singapore students, was a great opportunity for me to get to know fellow students intimately and form lasting friendships. My truly great friends included Koh Eng Kwang, Mori, Utam Singh, Wee Seong Kang, Thambirajah, Paramasivam, K.Kandiah, John Muthiah, Tan Boon Tat, Paramsothy and James Sabapathy. Unfortunately five of them died prematurely.

During my first year we Dr. Winstedt, the Principal, wanted us to form a Students’ Union, organise extracurricular activities and make representations to him on matters concerning our hostel life. Singapore students were more numerous than those from the Malayan States. Soo Ban Hoe proposed me to the post of Chairman and I was elected. I was surprised that subsequently he opposed many of my proposals for activities while most of the others supported me.

I captained the cricket team in all the three years. For most of the time, I was the bowler at one end with Stanley Stewart, who was brilliant, at the other. Additionally, I was in the hockey team, while for soccer I was in the second team.

I was delighted when the Final Examination arrived and I passed all subjects. More importantly, I had learnt to survive, value self-reliance and character, appreciate real friendship and accept adversity and hostility as part and parcel of life.

Reflections

Fortunately, during the five years preceding my entry into Raffles College I had immersed myself in reading which included much that was seriously religious and moral. I was striving to absorb principles and suppress evil inclinations. I want, however, to avoid creating any impression that I considered myself superior to others in morality. I had to whip myself to rise to the level of many around me I admired. I had read somewhere that a man becomes what he thinks. This inspired me to conceive the kind of teacher I wanted to be. Long after I had retired, I read in Mahatma Gandhi’s Art of Living, “the desire to improve ourselves for the sake of doing good to others is truly moral.” “The highest moral law is that we should unremittingly work for the good of mankind.” “Man becomes great exactly in the degree in which he works for the welfare of his fellow men.” Again, I hope you do not think that I am trying to say, “I am holier than thou.” I cannot deny that I wanted also to earn the highest possible salary and live the most comfortable life while giving my utmost service.

In spite of my refusal to go back to the University to do an Honours Course I gained promotions in the Education Service. I was the first Asian Principal of Raffles Institution. Later I held the post of Deputy Secretary/ Deputy Director, Education.